Best Practices for FDA IoT Cybersecurity Compliance

Post Summary

In 2025, FDA regulations for IoT medical devices demand strict cybersecurity measures to ensure patient safety and compliance. These rules, rooted in Section 524B of the FD&C Act and reinforced by the FDA's June 2025 guidance, require manufacturers to integrate cybersecurity throughout a device's lifecycle. Here’s what you need to know:

-

Key Requirements:

- Provide a detailed cybersecurity plan in premarket submissions.

- Maintain security through updates and vulnerability management.

- Include a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) listing all software components.

- Core Principles:

-

Why It Matters:

- Non-compliance can lead to denied FDA approvals or product recalls.

- Cyber threats, like ransomware or unpatched vulnerabilities, can disrupt care and compromise safety.

This article explains how to align with FDA cybersecurity expectations, covering risk management, secure updates, SBOM creation, and healthcare network integration. Following these practices helps protect patients and meet regulatory demands.

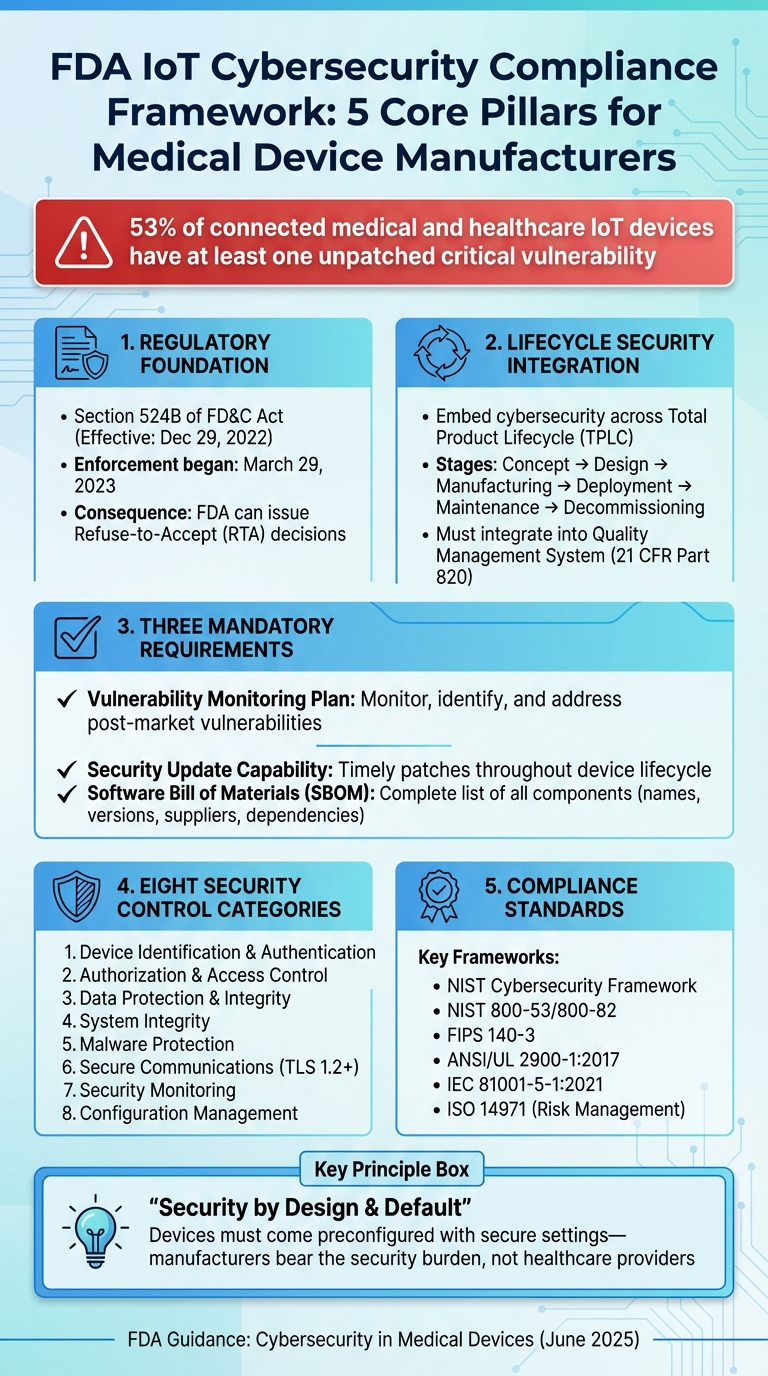

FDA IoT Cybersecurity Compliance Framework: 5 Core Pillars

Core FDA Cybersecurity Requirements for IoT Devices

Understanding Section 524B Cyber Device Obligations

On December 29, 2022, Section 524B of the FD&C Act introduced a federally mandated baseline for cybersecurity in connected medical devices [1]. This law reshaped premarket submission requirements by establishing three core cybersecurity obligations for manufacturers.

First, manufacturers must present a plan to monitor, identify, and address vulnerabilities that arise after a device reaches the market. This includes setting up coordinated vulnerability disclosure processes with clear response times and communication protocols. Second, they need to ensure devices remain secure throughout their entire lifecycle by implementing timely security updates and patches. Lastly, every premarket submission must include a detailed Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), outlining all components - whether commercial, open-source, or off-the-shelf - along with their names, versions, suppliers, and dependency relationships.

Section 524B(c) defines a "cyber device" as any device with sponsor-approved software that connects to other systems (via Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, USB, etc.) and is susceptible to cyber threats [2][6]. The FDA's 2025 final guidance expands this definition to cover any device containing software, such as embedded firmware or programmable logic, even if it isn’t actively network-connected. This interpretation means that nearly all modern IoT and software-equipped devices entering the U.S. healthcare market must meet rigorous cybersecurity documentation standards.

The FDA ties "reasonable assurance of cybersecurity" directly to its broader assessment of a device's safety and effectiveness. Inadequate cybersecurity alone can lead to a refusal of clearance or approval. Since March 29, 2023, the FDA has actively enforced this by issuing Refuse-to-Accept (RTA) decisions for premarket submissions that fail to include the required cybersecurity information under Section 524B. Alarmingly, industry reports reveal that 53% of connected medical and healthcare IoT devices have at least one unpatched critical vulnerability [3]. These requirements lay the groundwork for the FDA's comprehensive, lifecycle-focused security expectations outlined in its final guidance.

Key Themes in FDA Cybersecurity Guidance

The FDA's guidance builds on the statutory obligations of Section 524B, highlighting several overarching cybersecurity principles. The June 2025 final guidance, Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions, underscores the importance of integrating cybersecurity throughout a device's total product lifecycle (TPLC). This means cybersecurity should be embedded at every stage - from concept and design to manufacturing, deployment, maintenance, and eventual decommissioning - rather than being treated as a one-time premarket requirement. Activities like threat modeling, secure development practices, risk control selection, vulnerability testing, and management are emphasized as critical components under design controls, risk management, CAPA, and production processes in compliance with 21 CFR Part 820.

The FDA also promotes a risk-based approach focused on patient safety, urging manufacturers to prioritize cybersecurity measures based on their potential to prevent patient harm. Considering the deliberate nature of cyber threats, manufacturers are encouraged to assume that critical vulnerabilities can and will be exploited, rather than relying on statistical probabilities to assess risk.

Another key principle is the concept of security by design and default. Devices should come preconfigured with secure settings - such as least privilege access, strong authentication, and minimal service exposure - so that end users and healthcare providers don’t bear the burden of implementing additional security measures. To substantiate their cybersecurity efforts, manufacturers are encouraged to align with established frameworks like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, NIST 800-53/800-82, and FIPS 140-3. Additionally, referencing consensus standards such as ANSI/UL 2900-1:2017 and IEC 81001-5-1:2021 can help strengthen their claims.

Best Practices for Secure IoT Device Development

Implementing a Secure Product Development Framework

For medical IoT manufacturers, cybersecurity isn’t just an afterthought - it’s a critical part of the process. It must be integrated into the Quality Management System (QMS) under 21 CFR Part 820, touching every stage of development: from requirements gathering and design to implementation, verification, release, and postmarket surveillance. Security needs to be treated as a core design element [5].

A solid secure product development framework starts with formal governance. This means having leadership-approved cybersecurity policies that align with Section 524B obligations, covering areas like ensuring cybersecurity assurance, creating a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), and managing vulnerabilities [2][5]. To make this work, manufacturers should use established standards like IEC 81001-5-1 (health software security), UL 2900-1 (network-connectable products), and the NIST Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) [1][5]. These standards offer structured guidance on secure coding practices, maintaining build integrity, and setting configuration baselines - concepts that FDA reviewers are familiar with.

It’s essential to document security design inputs. These include identifying threats, meeting regulatory expectations, understanding clinical use contexts, and addressing interoperability needs. These inputs should then be traced through design outputs, test protocols, and risk controls. Clearly defined roles for security architects, engineers, and postmarket teams, along with maintained training records, ensure accountability and expertise throughout the process [2][5].

With this framework in place, the next step is to thoroughly assess risks and model threats to address the ever-changing cybersecurity landscape.

Risk Management and Threat Modeling

Building on secure design practices, manufacturers must adopt a risk management approach that spans the entire lifecycle of the device. Cybersecurity risk management extends beyond the usual ISO 14971 safety risk process, incorporating both safety and cybersecurity hazards. It emphasizes two key factors: severity and exploitability. This approach ensures that cyber exploits are connected to potential patient harm [2][6][5].

The FDA’s 2025 guidance prioritizes severity and exploitability over statistical likelihood, acknowledging that cyber threats are deliberate and constantly evolving [6][5]. Manufacturers are encouraged to assume that critical vulnerabilities will be targeted and to design controls that anticipate these scenarios.

Threat modeling is not a one-and-done task - it’s a continuous process throughout the device lifecycle. Effective threat modeling starts with identifying assets (like patient health information, therapy parameters, or firmware), trust zones (such as the device, hospital network, and cloud services), and external interfaces (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, USB, APIs) [2][5]. Techniques like STRIDE or attack trees help systematically identify threats and link them to potential harm.

Common threat scenarios for medical IoT devices include unauthorized remote configuration changes (e.g., altering infusion pump dosages), ransomware targeting hospital networks, interception of monitoring data via unencrypted wireless protocols, and supply chain vulnerabilities from third-party software components listed in the SBOM [2][6]. Threat models should be updated whenever vulnerabilities emerge, significant software updates are made, interfaces change, or clinical workflows evolve [2][6].

A thorough security architecture must address eight key control categories: device identification and authentication, authorization and access control, data protection and integrity, system integrity, malware protection, secure communications, security monitoring, and configuration management [2][5]. Examples of practical implementations include:

- Unique device identities anchored in hardware roots of trust

- Role-based access control for clinicians and service personnel

- End-to-end encryption using TLS 1.2 or 1.3 with FIPS-validated cryptographic modules

- Secure boot with code signing

- Operating system hardening with minimal services

- Comprehensive audit logging [2][3][5]

Secure Update and Patch Management

Even with robust risk management, devices need a reliable update and patch strategy to stay secure over time. The FDA mandates that medical IoT devices must be updatable by default. If updates are not possible, manufacturers must provide strong justification and document compensating controls in the risk management file [5]. This requirement is critical, given that 53% of connected medical and healthcare IoT devices have at least one unpatched critical vulnerability [3].

To address this, cryptographically signed updates are essential. Devices must verify digital signatures using modern algorithms and keys managed under NIST FIPS 140-3 guidelines before applying updates [2][3]. Update delivery mechanisms must ensure integrity and authenticity, whether through mutual TLS, certificate pinning, or offline signed media in controlled environments [2][5].

Rollback protection is another must-have. It prevents attackers from reinstalling older, vulnerable firmware versions. Secure boot chains anchored in immutable or hardware-protected roots of trust offer an effective solution [3][5]. Emergency patches are equally critical. Manufacturers need clear criteria for emergency releases, streamlined validation protocols, risk-based testing, and rapid deployment timelines to address actively exploited vulnerabilities [2][3][5].

Testing the update mechanism is just as important. This includes static and dynamic code analysis, vulnerability scanning, penetration testing, and fuzzing. Document these efforts under standards like UL 2900-1 to simplify regulatory reviews [2][5][7][1]. These practices ensure that device security remains aligned with FDA cybersecurity requirements throughout both premarket and postmarket phases.

Building an FDA-Ready SBOM and Managing Vulnerabilities

Developing a Complete SBOM

Creating a solid Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) is a cornerstone of FDA cybersecurity compliance. Manufacturers are required to deliver a detailed SBOM that lists all software components used in their devices [1][3]. An FDA-ready SBOM includes metadata such as the component's name, version, supplier, license details, cryptographic libraries, and dependencies. For example, if an IoT infusion pump relies on an open-source TLS library, the SBOM should document the library’s name, version, where it is utilized (e.g., firmware, mobile app, or cloud backend), and its role in the device's overall architecture.

To maintain an accurate SBOM throughout the device's lifecycle, integrate automated software composition analysis (SCA) into your secure development practices. This ensures that every build generates an updated SBOM artifact. Contracts with third-party suppliers should mandate that they provide their own SBOMs and notify you of any significant changes or vulnerabilities. When integrating supplier SBOMs, remove duplicates, capture nested dependencies, and ensure transitive vulnerabilities can be tracked. Each released device version should have a locked SBOM baseline, while development branches maintain evolving SBOMs tied to change requests, threat models, and verification reports [5].

Organize your SBOM using machine-readable formats like SPDX or CycloneDX. These standards allow hospital security tools and governance platforms to process the data automatically [3]. Beyond listing components, an FDA-ready SBOM should also include security metadata such as mapped Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs), maintenance status, end-of-life dates, FIPS 140-3 validation, and update capabilities, enabling thorough impact analysis.

Vulnerability Monitoring and Coordinated Disclosure

Once an accurate SBOM is in place, monitoring vulnerabilities becomes a manageable task. Use automated tools to continuously compare SBOM components against threat intelligence feeds like the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) and vendor advisories [3]. A vulnerability management plan should define severity criteria, establish timelines for responses, and outline escalation paths from detection to resolution [1][2][3]. Regular reviews and exception processes ensure vulnerabilities are addressed promptly [2][5].

Triage should follow a risk-based approach, considering factors like technical severity, exploitability, and patient safety. While CVSS scores can provide a baseline, the clinical context is crucial. For instance, an exploit that delays or alters therapy, disrupts diagnostics, or poses risks to multiple patients requires special attention [5][7]. Risks classified as "uncontrolled" demand immediate action, including emergency patches and safety communications. On the other hand, "controlled" risks can often be managed through scheduled updates or existing mitigations. All triage decisions and their justifications should be thoroughly documented to support FDA inspections and postmarket audits [5].

A strong Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure (CVD) program is essential. This should include a clearly defined vulnerability disclosure policy, a dedicated reporting channel (like a security email or web form), service level agreements for acknowledging and addressing reported issues, and safe-harbor language to encourage good-faith research [1][2][5]. The CVD process should feed into internal workflows, updating threat models, SBOMs, and patch plans. FDA guidance highlights the need for timely external communication, such as issuing security advisories to healthcare providers when high-risk vulnerabilities are identified [3][5]. Aligning your CVD program with standards like ISO/IEC 29147 and 30111, and documenting these processes in quality system records, demonstrates compliance during FDA reviews.

Finally, establish secure communication channels with healthcare providers, group purchasing organizations, and security partners to quickly distribute vulnerability and patch information. Use standardized, machine-readable formats tied to SBOM data [3][5]. These advisories, referencing specific SBOM components and affected versions, help healthcare organizations assess risks in their environments. For instance, tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can automate SBOM ingestion, correlate vulnerabilities, and streamline remediation efforts, enhancing the cybersecurity of IoT devices.

sbb-itb-535baee

Integrating IoT Devices with Healthcare Networks and Risk Management

Designing for Healthcare Network Integration

When developing IoT devices for healthcare environments, it's essential to ensure they integrate smoothly into segmented healthcare networks. This means designing devices to operate within isolated VLANs, limiting open ports, and adhering to strict firewall rules. Devices should clearly outline required network services and remain fully functional behind firewalls and proxies.

All IP communications must utilize TLS 1.2 or higher with mutual authentication and cryptographic standards approved by NIST/FIPS 140-3. Outdated protocols and weak encryption methods should be avoided entirely. To align with hospital infrastructure, devices should support certificate-based authentication, secure remote updates (with code signing), and encrypted management interfaces.

A robust identity and access management system is equally important. Devices should implement role-based access control (RBAC), integrate seamlessly with directory services like Active Directory, and eliminate the use of shared credentials. Additionally, devices must generate detailed security logs for critical events - such as logins, configuration changes, and failed authentication attempts - and securely export these logs to hospital SIEM systems for monitoring and incident response. Including clear implementation guides that map device roles to typical hospital IT roles, along with sample log formats, can simplify integration and management.

Thorough documentation is a cornerstone for both FDA premarket submissions and hospital security evaluations. Manufacturers should provide artifacts like network topology diagrams, data flow diagrams (distinguishing PHI from non-PHI paths), port/protocol/service matrices, and configuration baselines tailored for segmented network setups. This includes sample firewall rules, time synchronization needs, and descriptions of cloud dependencies, with a focus on U.S. data residency. These practices help ensure devices are prepared for seamless integration while laying the groundwork for effective risk management.

Using Censinet for Cybersecurity Risk Management

To complement these design principles, Censinet RiskOps™ offers a specialized platform that aligns manufacturer cybersecurity efforts with the rigorous demands of healthcare networks. Acting as a cloud-based risk exchange, the platform enables secure sharing of cybersecurity and risk information among healthcare organizations, vendors, and over 50,000 medical device products.

With Censinet Connect™, manufacturers can share structured security documentation - such as architecture overviews, SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) data, and vulnerability management plans - with potential healthcare customers early in the sales process. This proactive approach not only speeds up security reviews but also demonstrates compliance with the FDA's lifecycle cybersecurity expectations.

"Healthcare is the most complex industry... You can't just take a tool and apply it to healthcare if it wasn't built specifically for healthcare."

- Matt Christensen, Sr. Director GRC, Intermountain Health

The platform also supports ongoing risk monitoring and collaborative remediation tracking. This allows manufacturers and healthcare organizations to manage vulnerabilities, track mitigation efforts, and maintain a high level of cybersecurity assurance across device deployments. When new vulnerabilities are identified in third-party components or device libraries, manufacturers can update risk profiles, issue vulnerability notices, and share remediation plans directly through the platform. This structured communication not only supports internal audits but also aligns with FDA inspection requirements, ensuring a streamlined approach to risk management.

Conclusion

Meeting FDA IoT cybersecurity compliance isn't just a regulatory box to check - it's a critical step in ensuring the safety and effectiveness of medical devices. Under Section 524B of the FD&C Act, the FDA has the authority to deny premarket approval if cybersecurity vulnerabilities are identified, and the agency is actively leveraging this power through Refuse to Accept (RTA) decisions [1][2][4]. For manufacturers, this means embedding cybersecurity into every stage of the device lifecycle, from the initial design phase to deployment, maintenance, and even end-of-life planning. These efforts lay the groundwork for safeguarding devices against evolving cyber threats.

To meet these expectations, manufacturers need to incorporate cybersecurity risk management into their Quality System, maintain a machine-readable SBOM (Software Bill of Materials), conduct continuous vulnerability assessments with coordinated disclosure processes, and regularly update threat models [1][2][5]. These practices aren't just about compliance - they're about protecting patients from real-world risks like delayed treatments, faulty monitoring, or inaccurate diagnostics caused by cyberattacks.

Designing devices in line with FDA guidance from the start can help avoid costly delays during premarket reviews. Adhering to established standards such as UL 2900-1, IEC 81001-5-1, and NIST cryptographic guidelines (FIPS 140-3) provides FDA reviewers with familiar benchmarks and demonstrates a commitment to robust security engineering [1][3][5].

For healthcare delivery organizations managing complex device ecosystems, platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify third-party risk assessments, monitor remediation efforts, and maintain visibility into cybersecurity risks that impact patient safety and protected health information (PHI). By adopting a structured and collaborative approach, organizations can uphold FDA-aligned risk management practices throughout the device lifecycle, ensuring both compliance and patient safety.

Ultimately, aligning secure development, testing, and documentation with FDA expectations does more than meet regulatory demands - it fosters trust among healthcare providers, insurers, and patients. Cybersecurity compliance is about safeguarding patient well-being and ensuring reliable device performance in a world where cyber threats are constantly evolving [1][2][4].

FAQs

What happens if a company doesn’t follow FDA IoT cybersecurity guidelines?

Non-compliance with FDA IoT cybersecurity guidelines can lead to severe repercussions for organizations. These can include regulatory actions like warning letters, financial penalties, or even mandatory product recalls. Such measures not only disrupt daily operations but can also tarnish an organization's reputation.

Beyond regulatory risks, ignoring these guidelines significantly heightens the chance of cybersecurity breaches. These breaches could endanger patient safety and compromise sensitive health information. Safeguarding both patients and their data is essential, making adherence to these guidelines a must for any organization handling IoT devices in healthcare.

What steps can manufacturers take to keep their IoT devices secure throughout their lifecycle?

To maintain the security of IoT devices throughout their lifecycle, manufacturers need to implement ongoing risk management strategies and perform regular security evaluations. This means ensuring timely updates for firmware and software, keeping an eye on device performance to spot vulnerabilities, and swiftly addressing any risks that emerge.

Using advanced cybersecurity tools - such as specialized platforms tailored for risk management in industries like healthcare - can make these tasks more efficient. Staying proactive and alert not only helps safeguard devices but also supports compliance with FDA premarket cybersecurity guidelines.

What is the importance of a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) in meeting FDA cybersecurity requirements?

A Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) plays a vital role in meeting FDA cybersecurity requirements by offering a clear inventory of all software components within a device. This level of transparency allows organizations to pinpoint vulnerabilities, evaluate risks, and apply security patches promptly.

Keeping an SBOM helps simplify incident response, improve security oversight, and showcase compliance with the FDA's premarket cybersecurity guidance for IoT devices. It serves as an essential resource for building trust and safeguarding connected medical technologies.