How State Laws Shape Digital Health Privacy

Post Summary

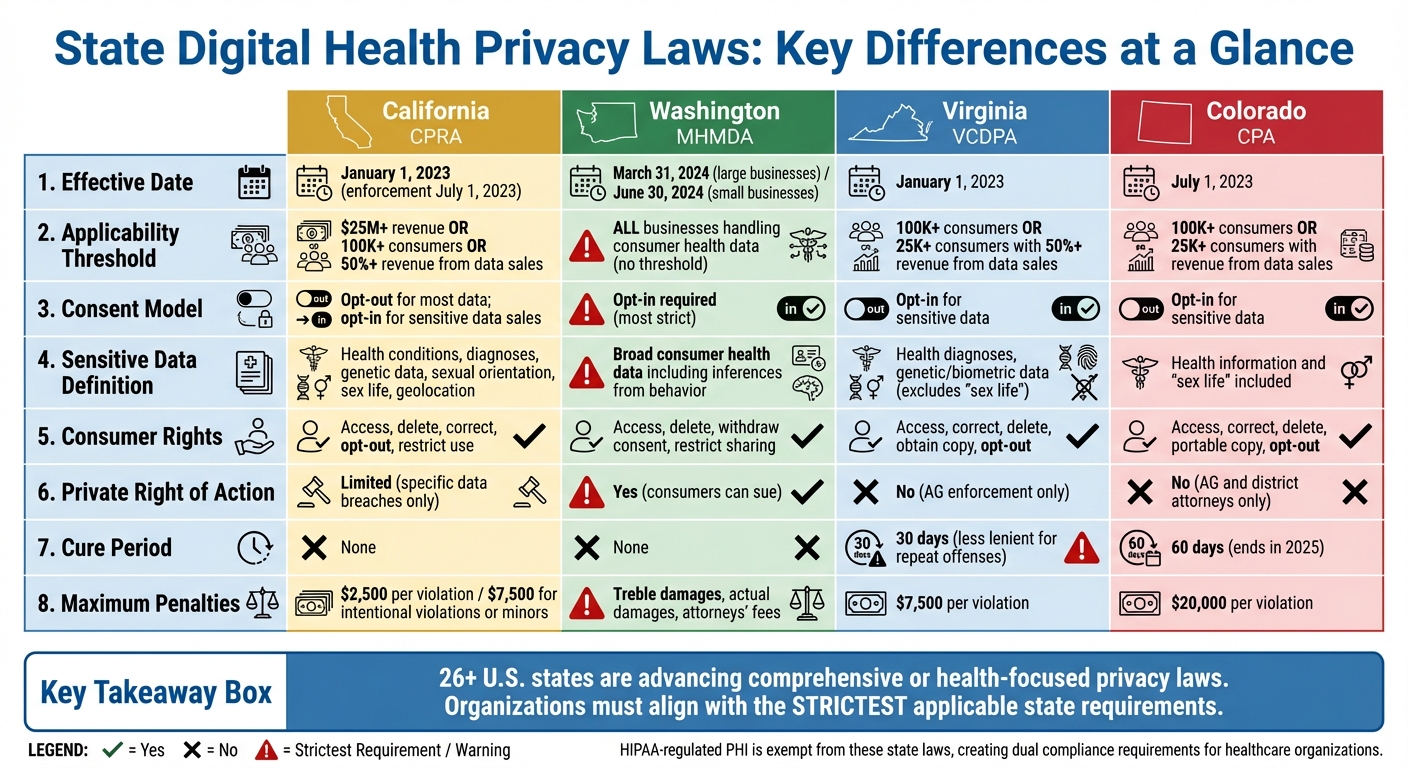

State laws are stepping in to protect digital health data where federal regulations like HIPAA fall short. With health information now coming from apps, wearables, and online platforms, states like California, Washington, Virginia, and Colorado have introduced privacy laws targeting this data. Here's what you need to know:

- California's CPRA: Broadly defines personal and sensitive health data, empowering consumers with rights to access, delete, and restrict its use.

- Washington's My Health My Data Act: Applies to all businesses handling health data, requiring opt-in consent and allowing private lawsuits.

- Virginia's VCDPA: Focuses on sensitive data but excludes some categories like "sex life", and limits enforcement to the Attorney General.

- Colorado's CPA: Covers health and sensitive data with strict opt-in consent rules and mandates for data protection assessments.

Each law has its own definitions, consent requirements, and penalties, creating challenges for businesses working across states. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ help streamline compliance by centralizing risk assessments and aligning with the strictest state laws.

Navigating these regulations requires careful planning, clear data processes, and robust security measures to avoid fines and protect consumer trust.

State Digital Health Privacy Laws Comparison: California, Washington, Virginia, and Colorado

1. California: CPRA and Health Data Regulations

California has established itself as a leader in setting strict standards for digital health data privacy.

Scope and Definitions of Health Data

California's regulatory framework for health data operates under three key laws: HIPAA, CMIA, and the CPRA. The CPRA, which came into effect on January 1, 2023, and began enforcement on July 1, 2023, defines "personal information" broadly. This includes any data that identifies or could reasonably be linked to an individual or household. The scope extends to data collected through health apps, wearables, telehealth platforms, and wellness programs. It also classifies "sensitive personal information" to include details like physical and mental health conditions, diagnoses, genetic data, sexual orientation, sex life, and precise geolocation.

While HIPAA-regulated entities are exempt from CPRA when it comes to protected health information (PHI), the CPRA still applies to other health-related data. For example, data from wellness apps, fertility or period trackers, and de-identified information used in marketing falls under its purview. This creates a layered compliance structure, where a digital health organization might need to adhere to HIPAA for clinical data, CMIA for patient medical information, and CPRA for broader consumer health data, depending on how the data is collected and used [5].

Individual Rights and Consent Requirements

The CPRA strengthens consumer control over health-related data. Californians have the right to request detailed information about the personal data collected from them, including information from symptom trackers, telehealth sessions, or wellness apps. They can also request the deletion of their personal information unless a valid retention exception applies [5].

Consumers are further empowered to correct inaccurate information, an essential safeguard when health-related data is used for personalization or risk analysis. Additionally, the CPRA allows individuals to limit the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information. Companies must provide clear and accessible tools - like privacy dashboards or preference centers - so users can restrict secondary uses of their data. For instance, individuals can prevent their mental or sexual health information from being used for targeted advertising [5].

Data Governance and Security Obligations

Organizations handling health-related data under CPRA must maintain an organized data inventory that clearly separates HIPAA PHI, CMIA medical information, and CPRA-designated data [5]. They are expected to follow principles of data minimization and purpose limitation, ensuring that only necessary data is collected for specific purposes and avoiding secondary uses without obtaining new consent.

Security is another key requirement. Businesses must implement strong measures proportional to the sensitivity of the data they handle. This includes encryption, authentication protocols, and auditing processes, as well as administrative safeguards like risk assessments, third-party risk management, workforce training on privacy laws, and incident response plans. These measures help organizations navigate the complexities of multi-state compliance. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify this process by offering standardized vendor security assessments, benchmarking security practices, and supporting remediation efforts [5].

Enforcement Mechanisms and Penalties

The CPRA established the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) to oversee rulemaking and enforcement. This agency works alongside the California Attorney General to investigate violations involving health-related personal and sensitive information. Unlike many other state privacy laws, California does not provide a general "right to cure", meaning regulators can impose penalties without giving organizations a chance to fix the issue first [3].

The penalties can be steep - up to $2,500 per violation and $7,500 for intentional violations or breaches involving minors. A single incident affecting thousands of consumers can quickly lead to substantial financial consequences. While the CPRA's private right of action is mostly limited to specific data breaches involving non-encrypted or non-redacted information, health-related breaches meeting these criteria can also result in class actions and statutory damages, in addition to regulatory enforcement [3][5].

California's comprehensive approach to health data privacy underscores the differences in state-level regulations, a trend that continues with Washington's unique framework.

2. Washington: My Health My Data Act

Washington introduced the My Health My Data Act (MHMDA) on April 27, 2023. This law, which takes effect on March 31, 2024, for large businesses and June 30, 2024, for smaller ones, stands out because it applies to all businesses managing consumer health data - regardless of their size or revenue [7]. Its broad scope establishes detailed rules around how health data is defined, handled, and protected.

Scope and Definitions of Health Data

MHMDA takes a much broader view of health data compared to HIPAA. It includes any personal information related to a consumer’s physical or mental health. This can range from data collected by health apps, wearables, and trackers to biometric identifiers, location data near medical facilities, and even inferences drawn from browsing or purchasing behavior [7].

For example, session data from a virtual mental health platform or tracking pixels on a hospital’s appointment scheduling page would now be considered consumer health data under this law. This means organizations like wellness apps, telehealth platforms, and digital marketing tools - often outside HIPAA’s reach - are now subject to regulation [7].

Individual Rights and Consent Requirements

MHMDA grants consumers significant control over their health data. People can request access to their data, delete it, withdraw consent, and restrict its sharing [7]. Businesses must also provide clear and transparent privacy notices, outlining what data they collect, why they collect it, who they share it with, and how individuals can exercise their rights.

A key shift under MHMDA is the requirement for opt-in consent before collecting or sharing health data. Unlike the opt-out models seen elsewhere, this law demands that consent be freely given, informed, and specific. Pre-checked boxes or combined consents are not acceptable. If a company plans to sell health data, it must obtain separate authorization, specifying what data will be sold, who will receive it, and for what purpose.

To comply, digital health platforms must refine their consent processes. This includes using clear "Manage Health Data" settings, layered notices in apps or patient portals, and explicit opt-in prompts before sharing any data [7].

Data Governance and Security Obligations

While MHMDA is primarily a privacy law, it also pushes businesses to adopt strong data security and governance practices. Organizations need to map and classify consumer health data, follow data minimization principles, and implement technical safeguards like encryption, access controls, and monitoring systems.

For businesses not covered by HIPAA, MHMDA sets a baseline for security comparable to HIPAA’s requirements. This includes robust access controls, regular vendor checks, and detailed agreements with third parties handling health data. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can help streamline these processes [7]. Companies must ensure that third parties comply with the law, prohibit unauthorized downstream sales, and conduct regular audits and due diligence [7].

Enforcement Mechanisms and Penalties

MHMDA includes enforcement by the Washington Attorney General and gives individuals the right to sue businesses for violations [7]. Consumers who can show harm caused by a violation can file lawsuits, significantly increasing the risk of litigation. Under Washington's Consumer Protection Act, businesses could face penalties including injunctive relief, actual damages, treble damages (up to certain caps), and attorneys’ fees.

This dual enforcement approach raises the stakes for healthcare and digital health organizations. A simple mistake - like misusing tracking pixels on a patient portal or targeting ads based on sensitive health data - could lead to regulatory investigations or costly lawsuits.

Washington’s approach signals a growing trend among states to address gaps in HIPAA and strengthen protections for digital health data. As more states introduce similar laws, companies operating across multiple states will face increasingly complex compliance challenges.

3. Virginia: Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA)

The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) became effective on January 1, 2023, marking it as one of the early state-level privacy laws following California's efforts [3][9]. This law applies to businesses operating in Virginia or targeting its residents, provided they process personal data for at least 100,000 consumers annually, or 25,000 consumers if over 50% of gross revenue comes from selling personal data [3][9]. This regulation introduces specific considerations for digital health organizations, particularly in how personal and sensitive data are defined and managed.

Scope and Definitions of Health Data

Under the VCDPA, personal data is broadly defined as any information that is linked or reasonably linkable to an identifiable individual [9]. The law also highlights a category of "sensitive data", which includes details like precise geolocation, genetic or biometric data, data from minors, and health diagnoses [5][9].

For digital health platforms, this means that much of the health-related information collected outside of HIPAA's jurisdiction falls under the VCDPA. Apps for wellness, mental health assessments, reproductive health tracking, and fitness frequently gather data that qualifies as sensitive, especially if it reveals health conditions or diagnoses [5][9]. However, HIPAA-regulated protected health information (PHI) is exempt from the VCDPA, creating a dual compliance challenge. For example, a hospital's electronic health records (EHRs) are governed by HIPAA, while its consumer-facing app must adhere to the VCDPA [4][5].

Individual Rights and Consent Requirements

Virginia consumers are granted several rights under the VCDPA, including the ability to access, correct, delete, and obtain a copy of their personal data, as well as the right to opt out of targeted advertising, data sales, and specific types of profiling [9]. When it comes to sensitive health data, businesses must obtain opt-in consent before processing this information. This consent must be explicit, informed, and freely given [5][9].

To comply, platforms need to implement clear and user-friendly methods for submitting data requests, verify identities before releasing records, and provide structured data exports (e.g., JSON or CSV) [9]. Additionally, organizations must ensure that consumers who opt out are flagged, so their health-related data is excluded from advertising or third-party sharing [7][9].

Data Governance and Security Obligations

The VCDPA emphasizes data minimization, requiring businesses to collect only what is necessary, while also mandating reasonable security measures, proper contracts with processors, and data protection assessments for high-risk activities like targeted advertising and profiling [6][9].

For organizations already adhering to HIPAA, many safeguards - such as encryption, access controls, and incident response - align with VCDPA requirements [2][5]. However, the VCDPA introduces a stronger focus on consumer privacy, extending to tools like patient-matching algorithms and health-risk scoring systems used in marketing [2][5]. To streamline compliance, businesses can integrate VCDPA assessments with existing HIPAA risk analyses by using a unified risk management approach. Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can help centralize vendor evaluations and ensure compliance across PHI, non-PHI patient data, clinical tools, and connected medical devices [2].

Enforcement Mechanisms and Penalties

The Virginia Attorney General exclusively enforces the VCDPA, and consumers are not granted a private right of action [3][9]. While the law initially allowed a 30-day cure period for businesses to address violations, regulators now demonstrate less leniency for repeat offenses or intentional non-compliance [3][10]. Civil penalties can reach up to $7,500 per violation, along with possible injunctive relief and attorneys' fees [6][9].

For healthcare organizations operating across multiple states, non-compliance with the VCDPA can result in hefty fines and reputational harm, particularly when sensitive health data is involved. This underscores the importance of robust risk management strategies to navigate the complexities of multi-state regulations effectively.

4. Colorado: Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), which went into effect on July 1, 2023, introduces a robust set of privacy protections for individuals in Colorado [9][10]. This law applies to businesses operating in Colorado or targeting its residents, provided they process data from 100,000 or more consumers or 25,000 or more if revenue is derived from data sales [9][10]. For digital health organizations, the CPA imposes new compliance requirements that go beyond the scope of HIPAA.

Scope and Definitions of Health Data

The CPA defines personal data as any information that can be linked or reasonably linked to an identified or identifiable individual [9]. It also creates a specific category for "sensitive data", which includes certain health-related markers. While similar to definitions in other state privacy laws, the CPA’s scope is broader than HIPAA’s definition of Protected Health Information (PHI) [5][9].

This distinction is particularly relevant for digital health platforms like wellness and fertility apps, which often collect data classified as sensitive under the CPA [5]. However, HIPAA-regulated PHI is exempt from the CPA, creating a split in compliance responsibilities. For example, a hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system is governed by HIPAA, but its consumer-facing wellness app must adhere to CPA requirements [4][5].

Individual Rights and Consent Requirements

The CPA grants consumers the right to access, correct, delete, and obtain portable copies of their data. It also allows them to opt out of targeted advertising, data sales, and certain profiling activities [9]. When it comes to sensitive health data, organizations must secure opt-in consent before processing it. This consent must be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous, requiring a clear affirmative action from the user [5][9].

To comply, organizations must develop secure, user-friendly systems for handling data requests within the required timeframes [5]. Additionally, maintaining detailed data inventories is essential to track where health, fitness, and behavioral data are stored, enabling structured exports in machine-readable formats. Staff training is also critical to ensure teams can distinguish between CPA and HIPAA-related requests, particularly when both frameworks apply to Colorado residents [4][5].

Data Governance and Security Obligations

For digital health companies operating across multiple states, maintaining effective data governance is key. The CPA requires reasonable administrative, technical, and physical security measures that align with the sensitivity and volume of the data being processed. The law also emphasizes data minimization and purpose limitation, meaning organizations should only collect the health-related data necessary for their stated purposes. For instance, collecting detailed reproductive histories for a general wellness newsletter would violate these principles [5][6][9].

To meet these requirements, organizations should implement role-based access controls, encryption for data in transit and at rest, and strong authentication protocols for systems managing Colorado residents’ health data [6]. Additionally, the CPA mandates data protection assessments for high-risk activities, such as combining geolocation data with reproductive-health app usage or using health-related profiles in algorithmic decision-making [9]. Starting July 1, 2025, stricter rules will apply to biometric data collection and processing, further tightening protections for health-related identifiers [8].

For multi-state healthcare organizations, tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can help centralize third-party risk assessments and monitor which vendors handle health-related data for Colorado consumers. These platforms ensure contracts and controls align with CPA requirements as well as other state laws [5].

Enforcement Mechanisms and Penalties

Enforcement of the CPA falls under the jurisdiction of the Colorado Attorney General and district attorneys, with exclusive authority - consumers cannot file private lawsuits [3][6][9]. Initially, the law included a 60-day cure period, allowing businesses to address violations after being notified. However, this grace period will end in 2025, giving regulators more leeway to enforce compliance immediately [3]. Civil penalties can reach up to $20,000 per violation, with each impacted consumer potentially counted as a separate violation, significantly increasing the stakes for large-scale data breaches [9].

For healthcare organizations operating across states, CPA violations involving sensitive health data carry both financial and reputational risks. To mitigate these risks, organizations should maintain documented risk assessments, detailed vendor-management records, and comprehensive incident-response plans. These measures not only demonstrate compliance but also help reduce potential enforcement actions. The importance of centralized compliance solutions will be explored further in the next section on risk management platforms.

sbb-itb-535baee

5. Censinet RiskOps™ Platform for Multi-State Compliance

Data Governance and Security Obligations

Censinet RiskOps™ steps in to tackle the complexities of complying with varying state laws governing digital health privacy. The platform simplifies multi-state compliance by unifying diverse data definitions, consent requirements, and security regulations. It meticulously inventories datasets and matches them to the most stringent state requirements, such as California's "sensitive personal information" and Washington's broader "consumer health data" definitions [5][7].

By embedding state-specific legal requirements into standardized risk assessments, the platform streamlines compliance for digital health tools, medical devices, and third-party vendors. For instance, when onboarding a telehealth vendor handling geolocation-linked reproductive health data, RiskOps™ ensures compliance by requiring a data protection impact assessment that aligns with the strictest state laws.

The platform's rules engine identifies where state laws exceed HIPAA protections. For example, certain states have additional safeguards for reproductive or sexual health data that HIPAA doesn't cover. In such cases, RiskOps™ applies tailored controls like explicit consent, stricter access restrictions, and purpose limitations. To stay ahead of emerging risks, healthcare organizations can run automated scans and vendor questionnaires, consolidating this information into a shared compliance resource for operations, compliance, and IT teams.

RiskOps™ also categorizes vendors by their risk level and jurisdiction, ensuring they meet state-specific mandates such as Washington's opt-in model or California's "service provider" requirements. Dashboards provide real-time tracking of vendor compliance, including cure timelines, incident responses, and contract terms, helping organizations prioritize attention to high-risk vendors.

"Censinet RiskOps allowed 3 FTEs to go back to their real jobs! Now we do a lot more risk assessments with only 2 FTEs required." [1]

- Terry Grogan, CISO at Tower Health

Another key feature is the unified evidence library, which organizes risk assessments, DPIAs, vendor due diligence, consent records, and incident reports by state-specific requirements. This library is invaluable in states like Washington, where private actions can be taken for unlawful health data practices. Detailed audit trails documenting consent, data-sharing decisions, and remediation actions demonstrate the implementation of robust controls and quick resolution of any gaps.

As privacy regulations evolve - currently, at least 26 U.S. states are advancing comprehensive or health-focused privacy laws [5][7] - RiskOps™ remains adaptable. It monitors regulatory changes and updates control catalogs, assessment tools, and risk scoring models to reflect new requirements, such as expanded sensitive data categories or revised compliance timelines.

"Not only did we get rid of spreadsheets, but we have that larger community [of hospitals] to partner and work with." [1]

- James Case, VP & CISO at Baptist Health

With this centralized approach, healthcare organizations are better equipped to meet shifting state standards while effectively managing risk.

Pros and Cons

Looking at the detailed analysis of state laws, it's clear that each offers its own set of advantages and challenges when it comes to digital health privacy. California's CPRA, for example, grants consumers robust rights like access, deletion, correction, and the ability to opt out of sensitive data sales. It's also backed by a dedicated enforcement agency. But here's the catch: the $25 million revenue threshold means smaller digital health startups are often left out, creating gaps in protection [5][7].

Washington's My Health My Data Act takes a different approach by requiring opt-in consent and permitting private lawsuits. While this broadens the scope of protection for Washington residents, it also increases compliance complexity and litigation risks for businesses handling health data [5][7].

Virginia's VCDPA offers a more business-friendly approach, with a 30-day cure period and enforcement limited to the Attorney General, reducing the chances of immediate lawsuits. However, its narrower definition of sensitive data - excluding "sex life" - means some areas, like reproductive and sexual health data from wellness apps, might not be as well-protected [3][5].

Colorado's CPA steps up by treating both health information and "sex life" as sensitive data, requiring opt-in consent and data protection assessments for reproductive health. On the flip side, its universal opt-out mechanism and a temporary 60-day cure period (set to expire in 2025) make implementation tricky and could lead to stricter enforcement down the line [3][5][8].

To navigate this fragmented landscape, platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ are stepping in. Their solution centralizes third-party and enterprise risk assessments, aligns vendor controls with requirements from CPRA, Washington's law, VCDPA, and CPA, and automates compliance tracking across jurisdictions [2]. Terry Grogan, Tower Health's CISO, shared:

"Censinet RiskOps allowed 3 FTEs to go back to their real jobs! Now we do a lot more risk assessments with only 2 FTEs required." [1]

That said, no platform can fully replace the need for legal expertise. Organizations still need to translate evolving laws into actionable policies and consent workflows. The initial setup for platforms like Censinet also demands significant effort in mapping data flows, systems, and vendors [4][5][7].

Here's a quick look at the pros and cons of these laws and platforms:

| Law/Platform | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| California CPRA | Strong protections for sensitive data (including health and sex life); broad consumer rights; dedicated enforcement agency. [3][5] | Excludes smaller businesses due to $25M+ revenue threshold; overlaps with HIPAA/CMIA require detailed data mapping. [5][7] |

| Washington My Health My Data Act | Covers consumer health data broadly; allows private lawsuits; strengthens reproductive health protections. [5][7] | Wide applicability increases compliance burden; strict consent and geofencing rules; higher litigation risks. [5][7] |

| Virginia VCDPA | Business-friendly with a 30-day cure period; AG-only enforcement lowers immediate litigation risk; structured similarly to GDPR. [3][5] | Sensitive data definition excludes "sex life"; higher thresholds limit applicability; may not set the strictest baseline. [3][5] |

| Colorado CPA | Considers health and "sex life" as sensitive data; mandates opt-in consent and data protection assessments; strong consumer rights. [3][5][8] | Operational challenges with opt-out and DPIAs; 60-day cure period ends in 2025, raising enforcement concerns; complex implementation. [3][8] |

| Censinet RiskOps™ | Tailored for healthcare, centralizes risk assessments; automates compliance tracking; reduces workload on staff. [1][2] | Requires ongoing legal guidance; resource-heavy initial setup; doesn't replace the need for governance and consent redesign. [4][5][7] |

While these state laws help address gaps left by HIPAA - especially for reproductive, behavioral, and wellness-app data - they also create a patchwork of regulations. This forces healthcare organizations to rethink their data strategies, consent processes, patient communication, and vendor contracts, all of which drive up compliance and tech costs. With at least 26 states advancing privacy protections and no federal standard in sight, centralized risk management tools are becoming increasingly crucial for organizations operating across multiple jurisdictions [7].

Conclusion

The world of digital health privacy is undergoing a dramatic transformation. HIPAA, once the cornerstone of health data protection, now serves as a starting point. State laws like California's CPRA, Washington's My Health My Data Act, Virginia's VCDPA, and Colorado's CPA have introduced new layers of privacy safeguards. These laws extend protections to health-related data that falls outside traditional definitions of protected health information - covering everything from wellness apps and period trackers to location-based data near clinics and health-related online activity.

For digital health vendors and healthcare organizations operating across multiple states, this patchwork of regulations creates significant challenges. Navigating varying consent requirements, consumer rights, enforcement rules, and definitions of sensitive data demands a strategic and meticulous approach. Organizations must classify data based on state-specific guidelines, implement nuanced consent processes (such as Washington’s opt-in requirements), and ensure compliance with California’s rules for sensitive data. On top of that, vendor contracts need to reflect these evolving obligations, and documentation must align with the strictest applicable standards. With at least 26 states pushing forward privacy protections and no federal law in sight[7], these complexities are only set to grow. The healthcare sector’s regulatory demands require tailored tools - not one-size-fits-all solutions borrowed from other industries.

Purpose-built tools are stepping in to ease these burdens. For example, Censinet RiskOps™ is designed specifically for healthcare risk management. It helps organizations centralize risk assessments, automate compliance tracking across different state laws, and benchmark cybersecurity measures. This tool also addresses risks tied to patient data, clinical apps, medical devices, and supply chains - all critical areas for healthcare organizations[1].

Looking ahead, the path forward requires a proactive approach. Organizations must align with the strictest rules across all applicable states, integrate privacy considerations into the earliest stages of product development, and maintain rigorous oversight of vendors - going well beyond HIPAA’s baseline requirements. By investing in centralized risk management systems now, healthcare organizations can prepare for the wave of new state laws and increasingly rigorous enforcement.

FAQs

How do state privacy laws impact digital health data compared to HIPAA?

State privacy laws often expand upon the federal guidelines established by HIPAA, introducing extra layers of protection for digital health data. While HIPAA sets the groundwork for securing patient information, many states go further by implementing stricter consent requirements, more rigorous data breach notification protocols, or broader patient rights concerning their health records.

The challenge for healthcare organizations? These state-specific rules can differ widely, creating a maze of compliance issues for those operating in multiple states. Navigating these variations is crucial - not just for meeting legal obligations but also for safeguarding sensitive patient information effectively.

What challenges do healthcare organizations face when complying with different state privacy laws?

Healthcare organizations face a tough challenge when it comes to managing inconsistent privacy laws across different states. Each state sets its own rules for handling patient data, protected health information (PHI), and cybersecurity. This creates a confusing patchwork of legal standards that can be difficult for organizations to navigate.

These differences don’t just complicate compliance - they also increase risks, drive up costs, and require significant resources to keep up with shifting regulations. On top of that, varying enforcement practices across states add another layer of complexity, making it even harder to maintain consistent data security and privacy protections nationwide.

How can healthcare organizations stay compliant with varying state privacy laws?

Healthcare organizations can navigate the maze of varying state privacy laws by using centralized platforms designed specifically for this purpose, like Censinet RiskOps™. These tools simplify risk assessments, provide better visibility, and make it easier to manage sensitive areas such as patient data and clinical applications - all of which are affected by state-specific regulations.

Staying compliant means keeping policies up-to-date as laws evolve, working closely with legal and compliance teams, and using industry benchmarks to ensure consistency. By following these practices, healthcare organizations can cut down on manual work, adapt more quickly to changes, and handle complex regulatory challenges with greater ease.