Top VCDPA Risks for Healthcare Providers

Post Summary

Healthcare providers in Virginia face unique challenges under the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA), which regulates personal data outside of HIPAA's scope. This includes wellness apps, patient portals, and marketing tools that collect sensitive health data. Key risks include mishandling reproductive health information, inadequate vendor oversight, and failing to meet consumer rights requirements. Non-compliance can result in penalties up to $7,500 per violation or lawsuits under Virginia's 2025 amendments protecting reproductive data.

Key Takeaways:

- VCDPA Scope: Covers personal data beyond HIPAA, like website analytics, wellness apps, and marketing databases.

- Sensitive Data: Requires opt-in consent for health, biometric, and reproductive information.

- Consumer Rights: Includes access, deletion, correction, and opt-out of targeted ads or profiling.

- 2025 Updates: Added protections for reproductive health data with statutory damages starting at $500 per violation.

- Vendor Risks: Third-party tools like analytics platforms must meet VCDPA standards, even if not under HIPAA.

Action Steps:

- Map all data collection activities, including PHI and non-PHI.

- Implement opt-in consent for sensitive data.

- Conduct Data Protection Assessments for high-risk processing like profiling or targeted ads.

- Update vendor contracts to align with VCDPA.

- Create clear workflows for handling consumer rights requests.

Healthcare providers must address these risks to avoid fines and ensure compliance with both HIPAA and VCDPA regulations.

Understanding VCDPA in the Healthcare Context

To navigate the complexities of the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) in healthcare, it’s essential to understand its three main concepts: controllers, processors, and sensitive data. A controller determines the purpose and means of processing personal data. For instance, a health system’s patient app that establishes policies for data collection and retention functions as a controller. On the other hand, a processor handles personal data strictly on behalf of a controller, following documented instructions. Examples include a cloud-based billing company managing patient payment data under a hospital’s direction or an IT vendor hosting a provider’s patient portal without using the data for its own purposes [5][13]. This distinction helps clarify responsibilities around data sensitivity and vendor obligations under the VCDPA.

Under the VCDPA, sensitive data includes personal information related to mental or physical health diagnoses, genetic or biometric identifiers, precise geolocation, sexual orientation, and data collected from children [5]. For healthcare providers, this extends to both clinical and non-clinical digital data. Examples might include a visitor’s location at a fertility clinic, behavioral data on a hospital website revealing a cancer diagnosis, or facial recognition technology used for patient check-ins [5][14]. Importantly, processing sensitive data requires explicit consumer opt-in consent [5].

However, it’s worth noting that HIPAA-regulated PHI and certain health records are exempt from VCDPA coverage, as are entities operating within HIPAA-regulated roles [1][5]. This exemption, though, is specific to the data and activity involved, not a blanket protection. For example, HIPAA-covered providers are still subject to VCDPA for non-PHI data like website analytics, patient engagement tools outside the designated record set, public wellness programs, or reproductive health data inferred from product purchases or online behavior [1][5][6].

In hybrid healthcare environments, entities often carry dual roles. For example, a telehealth platform might act as a controller for visit metadata used in analytics or marketing while simultaneously functioning as a processor for strictly HIPAA-governed PHI managed on behalf of a covered entity [5][13]. Mapping out each processing activity is essential to identify the correct obligations under VCDPA.

Healthcare providers should also pay close attention to third-party vendors and business affiliates. If a vendor uses data for purposes beyond the provider’s instructions - such as analytics, product development, or benchmarking across clients - they may be considered a controller (or joint controller) for those activities [5][7][13]. Contracts with such vendors must clearly define roles, outline permitted processing activities, prohibit unauthorized use or "sale" of data, and address targeted advertising restrictions. They must also ensure compliance with consumer rights requests [5][7]. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify this process by facilitating standardized third-party risk assessments and contract reviews for both PHI and non-PHI data across vendor portfolios.

1. Incomplete Scoping of VCDPA Applicability

Failing to fully scope the applicability of the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) can leave healthcare providers exposed to compliance risks. A common misconception is that being covered under HIPAA exempts organizations from VCDPA requirements. However, this only applies to HIPAA-protected health information (PHI). If your hospital, health system, or practice collects personal data from Virginia residents outside of HIPAA-regulated activities, your organization falls under the VCDPA’s jurisdiction [5].

Overlooked areas often include data collected through public website analytics, patient-facing apps, wellness programs, marketing databases, and tracking technologies. For instance, tracking cookies on a fertility clinic's website may gather consumer behavior data that isn’t classified as HIPAA-regulated PHI. Similarly, online appointment requests for reproductive health services or fitness program data collected via branded apps can trigger VCDPA obligations [5]. Digital platforms, such as hospital websites, group practices, retail health clinics, and telehealth services, are particularly at risk of missing these compliance requirements [7].

Another common pitfall is neglecting to inventory where third-party vendors process data from Virginia residents. Vendors like marketing automation platforms, survey tools, scheduling apps, and telehealth providers often handle personal data on your behalf - or use it for analytics or benchmarking. Without a thorough data mapping process, you might overlook whether your organization meets VCDPA thresholds. These thresholds include processing or controlling personal data of 100,000 Virginia consumers annually, or 25,000 if more than 50% of your revenue comes from selling that data [7].

Beyond standard analytics, certain data categories create additional challenges. For example, reproductive and sexual health data collected outside clinical workflows is often overlooked. Virginia’s 2025 amendment to the Virginia Consumer Protection Act (SB 754) specifically regulates "personally identifiable reproductive or sexual health information" collected in consumer transactions. This law operates alongside the VCDPA and includes a private right of action with statutory damages ranging from $500 to $1,000 per violation. Marketing campaigns, online quizzes, or product sales related to fertility, contraception, or gender-affirming care may fall under this regulation, requiring separate compliance assessments [3].

To address these gaps, consider using targeted risk management tools. Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can centralize vendor risk assessments, enabling you to map consumer data across both PHI and non-PHI systems. This approach helps identify activities that require VCDPA compliance or dual compliance, reducing the likelihood of incomplete scoping.

2. Mishandling Sensitive Health and Reproductive Data

Handling sensitive health and reproductive data presents another pressing challenge, especially when combined with the incomplete scoping issues of the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA).

Under the VCDPA, "sensitive data" covers a wide range of personal information, including mental or physical health diagnoses, precise geolocation, racial or ethnic origin, genetic or biometric data, religious beliefs, and information about children [16] [17] [14]. For healthcare providers, this means that data such as diagnoses, treatment plans, behavioral health records, and reproductive health details require explicit opt-in consent [16] [17] [14]. This step is crucial for maintaining compliance with the VCDPA's framework.

Unlike HIPAA, which allows the use of protected health information (PHI) for treatment and operational purposes under privacy notices, the VCDPA demands explicit consent for processing sensitive data that falls outside of PHI definitions [17]. Healthcare organizations accustomed to HIPAA's flexibility may need to create new consent mechanisms for areas like digital tracking, marketing, or processing reproductive health information that doesn't qualify as PHI [1] [16] [17].

Virginia’s 2025 amendment (SB 754) adds another layer of regulation by treating unauthorized collection or sharing of reproductive or sexual health data as fraudulent. Violations can lead to statutory damages ranging from $500 to $1,000 per incident, along with recovery for emotional distress [1] [3]. Even consumer-facing health tools - such as wellness apps, symptom checkers, or portals branded by providers but not integrated into official medical records - can fall under VCDPA’s requirements [1] [17].

Digital footprints, like tracking cookies on health-related web pages or linked e-commerce purchases, can inadvertently expose sensitive reproductive details [1] [3]. The law’s reach extends beyond clinical records to include website tracking data, cookies, and third-party pixels embedded in OB-GYN or reproductive health service pages that might share browsing behavior with advertising vendors [1] [3].

To comply, healthcare providers must implement robust opt-in consent processes for patient portals, online tools, and marketing platforms. Detailed consent logs should be maintained to document these interactions. Using cookie and tracking consent banners is particularly important on pages where tracking could reveal sensitive information. For added security, platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can centralize vendor risk assessments and map consumer data across both PHI and non-PHI systems, helping to mitigate the risk of mishandling sensitive health data. Tackling these consent-related challenges is a critical step before addressing broader vendor and third-party governance issues.

3. Weak Data Protection Assessments for High-Risk Processing

When dealing with high-risk data processing, taking a proactive approach is essential. The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) mandates that controllers conduct Data Protection Assessments (DPAs) for activities like targeted advertising, data sales, or profiling that could negatively impact consumers [2][5][13]. For healthcare providers, this means documenting these assessments before starting or modifying high-risk processing activities. These records must also be readily available for review by the Virginia Attorney General if needed [5][7].

DPAs should go beyond surface-level evaluations and provide a detailed risk-versus-benefit analysis. In healthcare, high-risk processing often includes AI-driven diagnostics using sensitive health or biometric data, large-scale handling of mental or physical health diagnoses, genetic data, targeted advertising based on health conditions, and automated decision-making that could affect access to care or insurance coverage [2][4][8][13]. Digital tools used in healthcare settings frequently fall under these requirements as well [1][6][13]. Proper documentation should cover processing activities, the types of data involved, potential risks (such as discrimination or denial of care), and the safeguards in place. This is critical for meeting both HIPAA and VCDPA requirements [2][5][7][8][9]. Additionally, healthcare providers must assess clinical safety risks, especially when AI or automated systems are used in diagnosis or treatment decisions [4][9]. Safeguards like encryption and access controls, as well as alternative approaches considered, should also be documented, along with measures to respect consumer opt-outs [2][5][7][8][9].

Some common pitfalls in DPAs include overlooking non-PHI (Protected Health Information) health data that falls under the law’s scope, conducting assessments too late in the process, treating DPAs as a mere formality with generic language, and failing to document how identified risks were mitigated or accepted by responsible parties [1][4][6][7][9]. It’s also important to evaluate all third parties with access to sensitive data [2][8][13]. This includes assessing their security and compliance measures, data-use restrictions, and how they handle onward data transfers [2][5][7]. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify third-party risk evaluations, making it easier for healthcare organizations to incorporate vendor risks into the broader DPA process.

To ensure DPAs are completed on time, healthcare providers should embed them into existing change-management and project-approval workflows [5][7][13]. While the VCDPA doesn’t specify how often DPAs must be reviewed, regulators expect them to be updated whenever significant changes occur - such as adopting new AI models, handling additional sensitive data, or responding to new legal standards [5][13]. As a best practice, high-risk DPAs should be reviewed at least annually or in line with broader risk management cycles. Updates should reflect new safeguards, incidents, or lessons learned [5][7][9]. These updated assessments should then be integrated into the organization’s overall risk management strategy.

4. Inadequate Governance of Vendors and Third Parties

HIPAA Business Associate Agreements (BAAs) focus solely on protecting PHI, but they fall short when it comes to other types of consumer data. To address this, healthcare providers should implement processing agreements that comply with the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA). These agreements should cover a broader range of data, including analytics, patient portal tracking, mobile app usage, and marketing information [2][5]. This expanded scope demands stricter oversight of vendors handling all types of data.

A healthcare legal survey revealed that nearly half of healthcare providers have experienced a third-party breach involving patient data [15]. Poor vendor governance increases the risk of enforcement actions, with civil penalties reaching $2,500 per violation and even higher damages for breaches involving reproductive or sexual health data [3][10]. These risks highlight the need for stronger VCDPA-specific contract provisions.

To address these challenges, contracts with vendors must include clear guidelines on data processing. They should specify processing instructions, ensure confidentiality, support consumer rights (such as access, deletion, correction, and opt-out options), assist with data protection assessments, and require data deletion or return upon contract termination [2][5]. Providers should also conduct risk-based vendor due diligence, mapping the personal and sensitive data each vendor collects, verifying their security measures and incident response plans, and assessing whether they process data for targeted advertising or profiling [2][5][8][9].

The challenge becomes even greater with vendors not covered by BAAs, such as website analytics tools, patient engagement platforms, or AI decision-support services. This need for tailored oversight is a recurring concern in the industry.

"Healthcare is the most complex industry... You can't just take a tool and apply it to healthcare if it wasn't built specifically for healthcare" [18].

To address this, providers must develop a comprehensive inventory and governance framework for all third-party vendors handling consumer data. Even when a BAA isn’t required, these vendors should be treated as processors under the VCDPA [1][2][6].

Specialized platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify this process. They automate vendor risk assessments, centralize security documentation, and track remediation efforts to ensure vendors align with VCDPA requirements.

"Censinet RiskOps allowed 3 FTEs to go back to their real jobs! Now we do a lot more risk assessments with only 2 FTEs required" [18].

5. Failure to Operationalize Consumer Rights Requests

The VCDPA provides Virginia consumers with five key rights: confirming whether their personal data is being processed and accessing it, correcting inaccuracies, deleting personal data, obtaining a portable copy of their data, and opting out of targeted advertising, data sales, and certain profiling activities that result in significant legal or similar effects [5]. Healthcare providers must respond to verified requests within 45 days. Extensions are allowed for complex or high-volume requests, but consumers must be notified of the delay and its reason. These responses must also be provided free of charge once per consumer each year [5]. Meeting these specific rights requires processes that go beyond the traditional scope of HIPAA.

Here’s where the challenge lies: HIPAA focuses solely on protected health information (PHI), but VCDPA obligations extend to a broader range of personal data. This includes data from website activity, patient portal analytics, mobile wellness apps, marketing databases, and reproductive health information collected outside HIPAA’s coverage. Many healthcare organizations mistakenly believe their HIPAA-compliant protocols are enough, but without tailored systems for handling VCDPA requests, they risk non-compliance. Providers lacking standardized intake systems, strong identity verification processes, and centralized tracking for these requests are particularly vulnerable - especially when dealing with sensitive health or reproductive data [5][3].

The stakes are high. Non-compliance can result in civil fines of up to $7,500 per violation. Mishandling reproductive or sexual health data carries additional penalties, including statutory damages ranging from $500 to $1,000 per violation, plus attorneys' fees [5][3].

If a provider denies a request, the VCDPA requires an appeals process. This includes documented procedures, an independent review, and a resolution within 60 days [5]. Providers must also inform consumers of their right to contact the Virginia Attorney General if the appeal is denied. Common missteps include incomplete data inventories that miss marketing or analytics systems, failure to ensure opt-outs are applied across all relevant vendors, and inconsistent management of profiling used for population health or risk scoring [2].

To stay compliant, providers need to establish clear and accessible channels, such as secure web forms or toll-free numbers. Workflows should be standardized to meet the 45-day response deadline, and decision matrices can help manage different data types effectively. Tracking metrics like request volume, response times, and denial rates can also bolster an organization’s readiness for regulatory scrutiny [5].

Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify these efforts by centralizing vendor data flows and ensuring timely responses to consumer rights requests. Implementing these measures not only aligns with compliance requirements but also strengthens overall risk management strategies.

6. Overreliance on HIPAA Safeguards and Legacy Security Controls

Many healthcare providers mistakenly believe that being HIPAA-compliant fully addresses their privacy obligations. This assumption can lead to regulatory blind spots. HIPAA focuses on protected health information (PHI) managed by covered entities and their business associates, specifically in contexts like treatment, payment, and healthcare operations [5]. However, the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) has a much broader reach, covering personal data related to Virginia consumers - even data that falls outside HIPAA’s scope [5].

This mismatch creates critical gaps. For example, data collected through online scheduling tools, wellness apps, or marketing platforms often isn’t covered by HIPAA but is subject to VCDPA regulations. Relying solely on HIPAA policies for these systems could mean overlooking essential VCDPA requirements, such as mechanisms for consumer rights, obtaining explicit consent for sensitive data processing, limiting data collection to specific purposes, and conducting comprehensive data protection assessments [5][7].

The two regulations also differ in their technical demands. HIPAA’s Security Rule prioritizes confidentiality, integrity, and availability through measures like encryption and access controls [9]. On the other hand, the VCDPA introduces additional responsibilities, such as collecting only necessary data (data minimization), using data strictly for disclosed purposes (purpose limitation), securing explicit consent for processing sensitive data, and performing formal assessments for high-risk activities like targeted advertising or profiling [2][5]. This means that a risk analysis tailored to HIPAA might not meet the VCDPA’s more detailed privacy impact documentation and mitigation requirements. Relying on outdated security controls can leave healthcare organizations exposed when it comes to VCDPA compliance.

Legacy security systems, often designed around electronic health record (EHR) platforms and clinical networks, tend to overlook non-clinical systems like web, mobile, and marketing platforms. These systems frequently lack robust controls, such as unified logging, thorough data mapping, and strict access management [9]. Without these safeguards, there’s a higher risk of over-collecting data, improper tracking, or unauthorized sharing - issues that could lead to enforcement actions by the Virginia Attorney General [1][3].

To close these gaps, healthcare providers should conduct a detailed data inventory. This process involves categorizing each system based on whether it handles PHI, non-PHI personal data, or data exempt from VCDPA requirements [5][7]. It’s essential to map out every point of data collection, from clinical systems to consumer-facing apps, and classify the data accordingly. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can extend risk assessments beyond traditional PHI environments, covering third-party apps, marketing platforms, and other non-PHI data flows. This ensures a more comprehensive approach to managing risks under both HIPAA and VCDPA regulations.

sbb-itb-535baee

7. Insufficient Transparency, Notices, and Consent Management

Healthcare providers must go beyond following vendor governance and DPA requirements by improving their transparency and consent practices.

Many providers mistakenly believe that their HIPAA Notice of Privacy Practices satisfies all transparency obligations. However, the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) requires more detailed notices. Under the VCDPA, organizations must publish privacy notices that clearly outline the categories of personal data being processed, the reasons for processing, how consumers can exercise their rights (such as access, deletion, correction, portability, and opt-out), and the types of third parties receiving the data. These notices must be written in plain, easy-to-understand language [5][7].

Transparency becomes even more critical when healthcare providers collect data outside of traditional clinical environments. Tools like patient portals, wellness apps, online scheduling systems, telehealth platforms, and marketing websites often gather data that doesn’t fall under HIPAA’s definition of protected health information. Information such as device identifiers, geolocation, browsing habits, or data from symptom checkers falls under the VCDPA’s scope [5]. Without clear notices explaining what data is collected and how it’s used, healthcare organizations risk enforcement actions.

Clear, detailed notices also lay the groundwork for effective consent management. The VCDPA mandates explicit opt-in consent for processing sensitive data, including health diagnoses, biometric information, and reproductive data, ensuring individuals approve each specific use [5]. Virginia’s 2025 amendment on reproductive and sexual health privacy raises the stakes further. It requires explicit consent for collecting, sharing, or selling reproductive and sexual health information, with a private right of action allowing individuals to sue for violations. Damages can range from actual damages to $500, or at least $1,000 for willful violations [3][10][20].

Avoid using third-party analytics or advertising pixels on patient-facing pages without obtaining clear, opt-in consent and providing transparent disclosures [1][6]. These tools can derive sensitive insights, such as health conditions, and failing to implement robust consent mechanisms can lead to significant legal risks. Providers must disclose when data is sold or used for targeted advertising and offer simple, one-click opt-out options [5]. Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can help by centralizing consent records and monitoring data-sharing practices.

To address these challenges, healthcare providers should create layered privacy notices that clearly distinguish between HIPAA-protected health information and consumer data governed by the VCDPA. Using relatable examples - such as “when you schedule an appointment online, we collect…” - can help patients understand how their data is handled [5][7]. Additionally, implementing consent management tools that capture explicit permissions for specific purposes (like care delivery, marketing, or analytics), maintain timestamped consent records, and allow users to revoke consent at any time is essential [1][5][6]. Strengthening transparency and consent practices not only ensures compliance with VCDPA but also supports a broader data governance framework.

8. Gaps in AI and Automated Decision-Making Governance

Healthcare organizations increasingly rely on AI for tasks like patient triage, risk scoring, prior authorizations, and eligibility decisions. Under the VCDPA, profiling refers to any automated evaluation of personal data that impacts a consumer's health, behavior, location, or finances [5]. When these AI-driven processes result in decisions with legal or significant effects - such as determining access to care, coverage, or financial responsibilities - they trigger additional obligations under the VCDPA, which providers may unintentionally overlook.

The VCDPA gives consumers the right to opt out of profiling when it leads to such impactful decisions. This means healthcare organizations must clearly disclose in their privacy notices where AI or algorithms influence critical care decisions. They also need to provide a straightforward way for consumers to exercise their opt-out rights. Additionally, profiling that could lead to discrimination, delays in care, or financial harm requires a documented data protection assessment before the AI is deployed. These assessments should cover the AI tool's purpose, the types of personal and sensitive data processed (e.g., health conditions or biometrics), potential risks, safeguards in place, and how consumer opt-out preferences will be enforced. As with other VCDPA requirements, maintaining proper documentation and offering clear consumer controls are essential for effective AI governance.

However, many healthcare organizations deploy AI tools - such as decision support systems, chatbots, and screening algorithms - without fully addressing their profiling obligations under the VCDPA. This often results in untracked systems, unclear accountability for AI-related risks, and missing data protection assessments. Without these safeguards, demonstrating compliance or handling opt-out requests can become a significant challenge.

To address these gaps, organizations should establish an AI registry to document each model's purpose and data sources. Forming a cross-functional committee to review AI tools before deployment and conduct periodic audits for bias and performance can further strengthen oversight. Privacy notices should clearly state when AI is in use, the data being analyzed, and how patients can opt out. Additionally, embedding VCDPA requirements into contracts with AI vendors ensures that compliance responsibilities are upheld.

Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can help healthcare organizations streamline AI-related due diligence, manage AI vendor catalogs, and simplify third-party risk assessments. These tools support governance practices that align with VCDPA requirements and integrate seamlessly into broader risk management strategies tailored to the healthcare sector.

9. Fragmented Incident Response and Breach Notification

Healthcare providers in Virginia face a tangled web of breach notification rules. For starters, HIPAA's Breach Notification Rule applies specifically to unsecured protected health information (PHI) held by covered entities and business associates. It requires notification within 60 days of discovering a breach. Meanwhile, the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) mandates reasonable data security practices and empowers the Virginia Attorney General to impose civil penalties of up to $7,500 per violation for security lapses involving personal data. Adding to the complexity, Virginia's general data breach law requires notifying affected residents "without unreasonable delay" when personal information - like Social Security numbers or financial account data - is compromised by unauthorized access [5]. These overlapping requirements call for a unified incident response strategy.

The VCDPA’s broader definition of "personal data" raises the stakes. Breaches that don’t meet HIPAA’s criteria can still fall under VCDPA enforcement. For example, issues like unsecured cloud storage or patient portal tracking might expose non-PHI data that triggers state-level scrutiny [1]. Consider this: in 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reported 725 large healthcare data breaches affecting over 133 million individuals. The average cost of a healthcare breach reached a staggering $10.93 million - the highest across all industries [5].

Fragmentation in incident response occurs when providers tackle HIPAA and VCDPA requirements in isolation. This disjointed approach mirrors the vendor governance gaps discussed earlier and leaves compliance vulnerabilities exposed. Common pitfalls include triage forms that only assess PHI involvement, legal reviews narrowly focused on HIPAA while ignoring VCDPA obligations, and vendor management processes that fail to account for the states of affected residents or coordinate across multiple regulatory frameworks [5].

To overcome these challenges, healthcare providers need a cohesive incident response strategy. This involves creating a unified policy that categorizes incidents by data type - whether it’s PHI, other personal data, sensitive information under VCDPA, or financial data. The policy should immediately identify the states of affected individuals and direct incidents to a multidisciplinary team, including experts in privacy, security, legal, compliance, and communications. This ensures all regulatory requirements are addressed in a consolidated manner [5].

An effective incident response playbook should include decision trees that guide actions for HIPAA breach analysis, triggers under Virginia and other state breach laws, and VCDPA-related considerations like inadequate security practices or unlawful data processing. Clear RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) roles should designate a single coordinator to oversee regulatory analyses and maintain consistent communication with patients, regulators, and the media. Aligning incident response efforts with vendor risk management is another critical step toward a unified compliance framework.

Healthcare-specific platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can be game-changers. These tools centralize third-party and enterprise risk data, covering everything from vendor inventories and clinical applications to data flows involving both PHI and other personal data. By streamlining assessments and fostering collaborative risk management, such platforms help providers quickly scope incidents, identify vendors handling Virginia residents' data, and ensure compliance with HIPAA, VCDPA, and other state breach laws.

10. Lack of Ongoing Governance, Training, and Monitoring

VCDPA compliance isn’t something you can check off once and forget about - it’s an ongoing commitment that demands consistent attention. The Virginia Attorney General can impose fines of up to $7,500 per violation, making it clear that compliance missteps can carry a hefty price tag [5][19]. Yet, many healthcare providers approach VCDPA as a one-and-done project, completing an initial compliance effort but failing to adapt as data practices evolve and new regulations emerge. This dynamic environment requires a solid framework for governance, training, and monitoring.

Governance: Building a Strong Foundation

Effective governance starts with a clear structure. Healthcare organizations should form a cross-functional steering committee that includes representatives from compliance, legal, IT security, clinical leadership, and vendor management. This group should meet regularly to discuss data protection assessments, vendor risks, incidents, and regulatory updates. Assigning accountability is key - appoint a privacy officer and a security officer with clearly defined roles and direct reporting lines to executive leadership or the board.

Training: Keeping Everyone Informed

Training isn’t a one-time event either. Employees need VCDPA training during onboarding and annually, with extra sessions whenever significant changes occur. These sessions should cover how to identify sensitive personal data (such as health, biometric, and children’s information), handle consumer rights requests, and navigate restrictions on using health data for targeted advertising. Vendor due diligence responsibilities should also be a focus. And with the rise in fraud and phishing threats, continuous education on recognizing these schemes is essential to protect both the organization and its patients.

Monitoring: Staying Ahead of Risks

Regular monitoring is crucial to maintaining compliance. Organizations can implement practical measures like periodic internal audits, automated logging of consumer rights requests and disclosures, system configuration reviews, and centralized registers for tracking data processing activities and risk assessments. Metrics such as the volume of consumer rights requests, vendor contract compliance rates, training completion rates, and audit outcomes can help gauge the effectiveness of your compliance program. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can centralize risk data, benchmark cybersecurity performance, and track remediation progress.

"Benchmarking against industry standards helps us advocate for the right resources and ensures we are leading where it matters" [18].

Documentation: The Backbone of Compliance

Comprehensive documentation ensures your compliance efforts are sustainable and adaptable. Maintain a secure, centralized repository for data inventories, processing records, policies, assessments, contracts, training logs, consumer request records, incident reports, and meeting notes. This library should have strict access controls and retention schedules to ensure readiness for regulatory inquiries.

The stakes are high, especially with Virginia’s 2025 amendments, which introduced stricter rules for processing minors’ data and added protections for reproductive and sexual health information. These changes include a private right of action and statutory damages, emphasizing the importance of staying on top of regulatory updates [3][11][12].

Failing to maintain up-to-date documentation and processes leaves healthcare providers vulnerable to enforcement actions or lawsuits as regulations and risks continue to shift.

Comparison Table

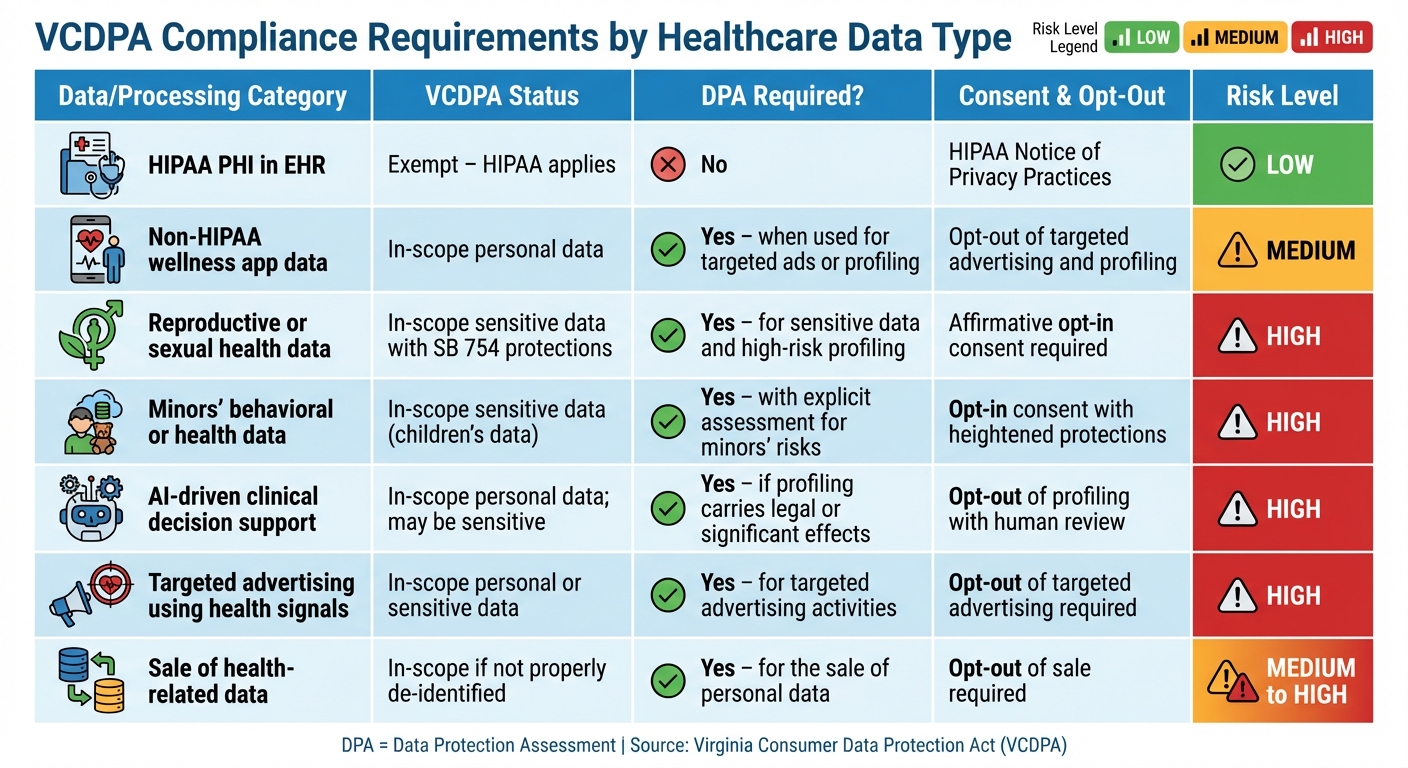

VCDPA Compliance Requirements by Healthcare Data Type

Healthcare providers handle a variety of data types and processing activities, each with specific obligations under the VCDPA. The table below summarizes these requirements across common healthcare data scenarios, highlighting key compliance actions and associated risk levels.

| Data / Processing Category | VCDPA Status | DPA Required? | Consent & Opt-Out | Key Compliance Actions | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIPAA PHI in EHR (treatment, payment, operations by covered entities) |

Exempt – HIPAA applies | No | HIPAA Notice of Privacy Practices | Maintain HIPAA safeguards; no additional VCDPA obligations | Low |

| Non-HIPAA wellness app data (steps, heart rate, sleep tracking on patient portal) |

In-scope personal data | Yes – when used for targeted ads or profiling | Opt-out of targeted advertising and profiling | Conduct a data protection assessment; update privacy notices; implement opt-out mechanisms and ensure robust vendor contracts | Medium |

| Reproductive or sexual health data (fertility tracking, abortion care information, sexual health teleconsults) |

In-scope sensitive data with additional VCPA SB 754 protections | Yes – for sensitive data and high-risk profiling | Affirmative opt-in consent required prior to collection, disclosure, or sale | Conduct a DPA; obtain explicit consent without relying on "necessary processing" exceptions; note the risk of a private right of action [3] | High |

| Minors' behavioral or health data (pediatric patient portals, teen mental health apps) |

In-scope sensitive data (children's data) | Yes – with an explicit assessment for minors' risks | Opt-in consent with heightened protections for profiling | Conduct an enhanced DPA addressing minors' unique risks; limit profiling and tracking; secure parental consent where applicable | High |

| AI-driven clinical decision support (readmission risk scoring, eligibility determinations) |

In-scope personal data; may be sensitive if health diagnoses are involved | Yes – if profiling carries legal or other significant effects | Opt-out of profiling with human review recommended | Conduct a DPA; assess bias and fairness; document model logic and provide mechanisms for appeal or override | High |

| Targeted advertising using health signals (retargeting based on patient portal visits, sharing hashed emails with ad networks) |

In-scope personal or sensitive data | Yes – for targeted advertising activities | Opt-out of targeted advertising required | Conduct a DPA; obtain proper consent for processing sensitive data; update vendor contracts and provide clear opt-out options | High |

| Sale of health-related data to analytics vendors (sharing de-identified or pseudonymous data with third parties for research or marketing) |

In-scope if not properly de-identified under HIPAA | Yes – for the sale of personal data | Opt-out of sale required | Conduct a DPA; verify de-identification standards; enforce contractual controls and ensure transparent notices | Medium to High |

This table builds on earlier discussions by outlining compliance steps and risk levels for each data type. For digital health tools outside HIPAA's reach, VCDPA requirements now apply, making compliance essential. For example, AI-driven decisions impacting care coordination, eligibility, or financial assistance require thorough documentation of model logic, bias evaluation, and human oversight to reduce risks.

Vendor relationships also remain a critical focus. Whether using cloud-hosted EHR platforms, marketing tools, or remote patient monitoring systems, healthcare organizations must ensure VCDPA-compliant data processing agreements. These agreements should outline confidentiality obligations, processing instructions, support for consumer rights requests, and audit provisions. Tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify third-party risk assessments, benchmark vendor security, and track remediation efforts for both PHI and non-PHI data.

High-risk activities - such as handling reproductive health data, minors' information, AI-driven decisions, and targeted advertising - require immediate attention. Comprehensive risk assessments and robust contractual controls are essential to navigate these challenges effectively.

Conclusion

Healthcare providers face a variety of compliance risks under the VCDPA that go well beyond the requirements of HIPAA. Misjudging which data and activities are covered by the law, improperly handling sensitive reproductive and sexual health information under Virginia's SB 754, poor vendor oversight, and underdeveloped AI governance can all lead to enforcement actions by the Virginia Attorney General. These risks carry financial penalties of up to $2,500 per violation and, in the case of SB 754, private lawsuits with statutory damages starting at $500 per affected individual [3].

HIPAA alone doesn’t provide enough protection because the VCDPA governs personal data of Virginia residents that often falls outside the scope of PHI. Information from wellness apps, marketing campaigns, patient portal analytics, AI-driven tools, and reproductive health data processed in non-clinical settings requires opt-in consent, thorough Data Protection Assessments, and clear opt-out options.

To tackle these challenges, healthcare providers need a structured and repeatable compliance approach. Centralizing governance for tasks like data mapping, risk assessments, vendor management, and incident response allows organizations to extend controls across new technologies, services, and state privacy laws without unnecessary duplication or gaps. Platforms such as Censinet RiskOps™ are designed to help healthcare organizations meet these requirements by streamlining third-party risk assessments, maintaining detailed inventories of vendors and data flows, and identifying vendors that handle sensitive or reproductive health data. General-purpose compliance tools often fall short in addressing the unique complexities of healthcare, such as clinical applications, medical devices, and patient data.

This proactive approach not only reduces current risks but also prepares providers for evolving regulatory landscapes. The VCDPA is part of a growing wave of state privacy and AI regulations, with particular focus on health data, reproductive information, and automated decision-making. By investing in adaptable, data-focused governance, robust training programs, and continuous monitoring, healthcare providers can stay ahead of new requirements. This readiness builds a strong foundation for digital trust, responsible use of AI, and patient-centered care in the years to come.

FAQs

What types of personal data does the VCDPA cover that HIPAA does not?

The VCDPA governs personal data that goes beyond the limits of HIPAA, covering details like personal identifiers, internet activity, geolocation, and data used for profiling or targeted advertising. While HIPAA is specifically concerned with protected health information (PHI), the VCDPA casts a wider net, regulating various types of consumer data to uphold privacy rights in areas outside of healthcare services.

For healthcare providers, this means compliance isn’t just about patient care. They also need to consider how they handle data from sources like marketing analytics or online interactions to meet the VCDPA's requirements.

What steps can healthcare providers take to stay VCDPA-compliant when working with third-party vendors?

Healthcare providers can ensure VCDPA compliance when working with third-party vendors by adopting a focused approach to managing risks. Begin with thorough risk assessments to pinpoint any weaknesses in how vendors handle sensitive information. It's also crucial to include specific privacy and security requirements in contracts that align with VCDPA regulations.

To maintain compliance over the long term, establish regular monitoring of vendor practices and work closely with them to address new challenges as they arise. Using specialized tools tailored for healthcare risk management can simplify this process, safeguarding patient data while meeting regulatory requirements efficiently.

What are the risks of mishandling sensitive reproductive health data under the VCDPA?

Mishandling sensitive reproductive health data under the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) can lead to serious consequences for healthcare providers. These include steep fines, regulatory penalties, and even lawsuits for breaching privacy rights.

But the impact goes beyond legal and financial penalties. Poor data management can undermine patient trust, harm your organization's reputation, and draw unwanted attention from regulators. Safeguarding sensitive data isn’t just about meeting legal requirements - it’s a critical step in building strong patient relationships and reducing potential risks.