FDA vs. EU MDR: Medical Device Patching Rules

Post Summary

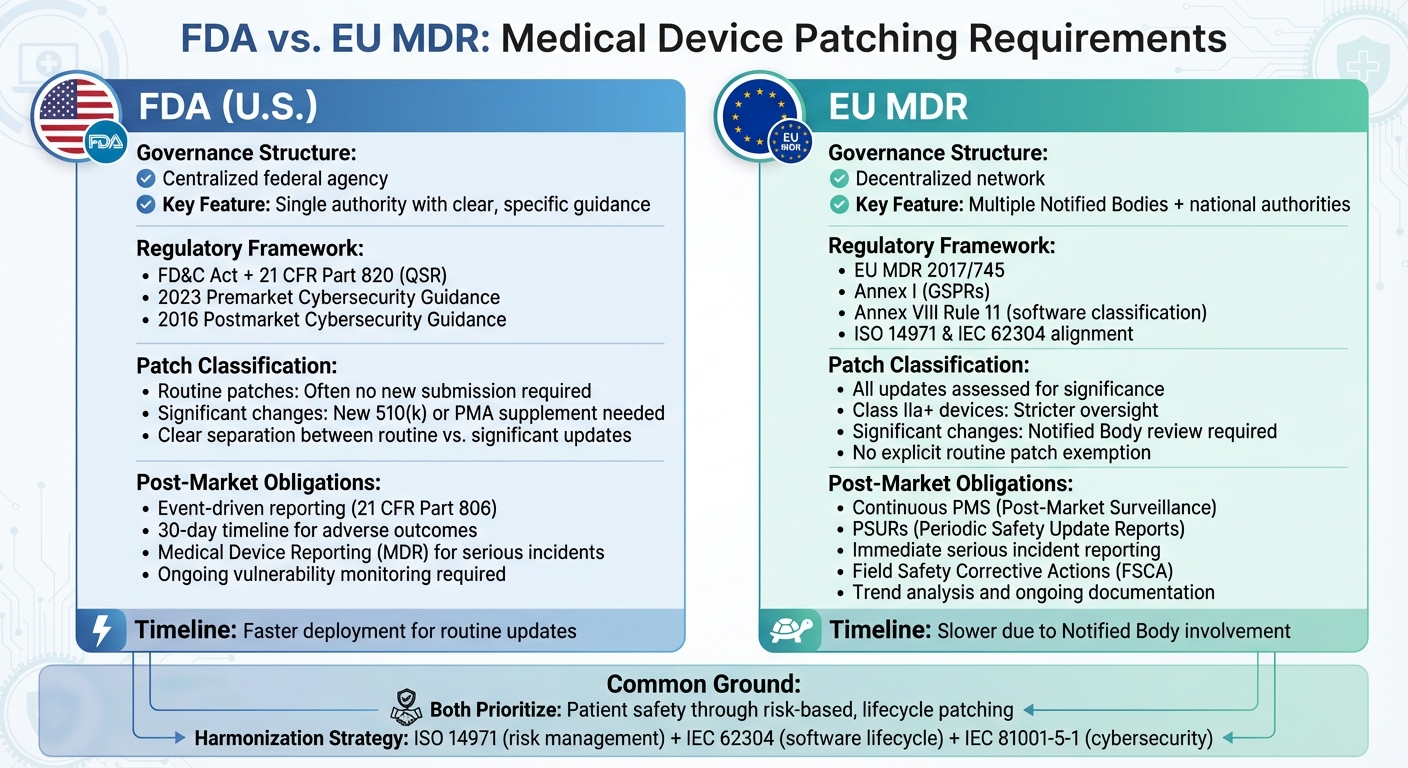

Medical device patching is a critical process to address software vulnerabilities while ensuring patient safety. The U.S. FDA and EU MDR take different regulatory approaches, creating challenges for manufacturers aiming to comply with both. Here’s what you need to know:

- FDA (U.S.): Focuses on a lifecycle approach, requiring secure design, premarket threat modeling, and ongoing postmarket monitoring. Routine patches often don’t need new submissions unless they affect device safety or performance.

- EU MDR (EU): Embeds patching within broader safety and risk management frameworks. Every update is assessed for its impact, with higher-risk devices requiring stricter oversight and possible Notified Body review.

Quick Overview

- FDA: Centralized system with clear guidance, faster patch deployment for routine updates.

- EU MDR: Decentralized system with stricter classifications, slower patch timelines due to Notified Body involvement.

Both frameworks prioritize patient safety but differ in execution. A unified strategy based on global standards like ISO 14971 and IEC 62304 can streamline compliance, ensuring manufacturers meet both sets of requirements efficiently.

FDA Requirements for Medical Device Patching

FDA Regulatory Framework for Patching

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act lays the groundwork to ensure medical devices remain safe and effective throughout their lifecycle. This includes requiring manufacturers to actively address cybersecurity vulnerabilities through well-documented patching processes[2]. The Quality System Regulation (QSR) outlined in 21 CFR Part 820 brings these expectations to life by mandating design controls, corrective and preventive action (CAPA) processes, complaint handling systems, and risk management procedures. Under these rules, patches are treated as formal design changes and must adhere to documented risk analysis, verification and validation (V&V), and configuration management protocols proportional to the associated risks[5].

Further guidance from the FDA builds on this framework. The 2023 premarket guidance, "Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions," requires manufacturers to incorporate secure update mechanisms - like authenticated patch delivery and detailed update plans - into device design and submission materials[3]. Meanwhile, the 2016 postmarket guidance, "Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices," emphasizes that addressing vulnerabilities and deploying patches is not optional but a critical part of postmarket quality and risk management[1][5].

These regulations ensure manufacturers approach patching with the same level of diligence as other design and safety processes.

Patch Planning and Execution Under FDA

Effective patching begins with early integration into risk management and threat modeling. Manufacturers must anticipate, prioritize, and address vulnerabilities proactively[1][3]. Premarket submissions should detail secure update mechanisms, such as authenticated code signing, encryption, and rollback protections, to prevent unauthorized or malicious updates[3][5]. Additionally, the logistics - whether updates are remote or on-site, automatic or manual - and any dependencies on hospital infrastructure must be clearly documented to ensure compatibility with clinical workflows[1].

Under 21 CFR Part 820, each patch undergoes a risk-based assessment to evaluate its impact on safety and essential performance[2]. This includes identifying potential unintended consequences, such as system instability, interoperability challenges, or workflow disruptions[2][5]. Deployment plans must include instructions for installation, prerequisites, rollback procedures, and clear communication of patch priorities and timelines to healthcare delivery organizations (HDOs). All of this must be documented in the device history file and CAPA records[1][2].

These efforts feed into a continuous postmarket process focused on monitoring and managing risks.

FDA Postmarket Cybersecurity Guidance

The FDA's postmarket cybersecurity guidance emphasizes an ongoing, risk-based approach to vulnerability management. This process aligns with QSR requirements and industry standards like ISO 14971 and IEC 62304[1][3]. Manufacturers are expected to maintain robust systems for monitoring and triaging vulnerabilities. This includes coordinated disclosure programs, external monitoring through Information Sharing and Analysis Organizations (ISAOs), and the involvement of dedicated product security teams[1][5]. Vulnerabilities are prioritized based on their risk to patient safety, with critical issues - such as remotely exploitable flaws that could cause serious harm - receiving accelerated remediation and communication to stakeholders[1].

Testing plays a crucial role in this process. Cybersecurity-focused verification, including regression testing, ensures patches are effective. Clinically significant patches should also be validated in representative environments before being deployed in the field[5]. Routine updates that restore previously validated controls generally do not require new premarket submissions unless they introduce additional risks[5][2]. However, manufacturers must document their risk-based rationale and provide evidence of verification and validation to explain whether a patch necessitates a new submission[2].

For vulnerabilities that could result in patient harm, manufacturers must determine if they qualify as reportable adverse events or device malfunctions under the Medical Device Reporting (MDR) requirements in 21 CFR Part 803[2]. If addressing a vulnerability involves correcting or removing a distributed device, manufacturers must assess whether the action falls under 21 CFR Part 806 and whether it should be reported as a recall or field action[1]. The FDA also warns that unmitigated vulnerabilities capable of causing serious injury or death may be classified as device defects, potentially triggering enforcement actions or recalls[5].

Healthcare delivery organizations (HDOs) must align their patch management practices with these FDA requirements to ensure patient safety. Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify this process by helping HDOs maintain device inventories, apply patches in a timely and risk-prioritized manner, validate patches in clinical environments, and implement compensating controls when immediate patching isn’t feasible[5]. Censinet RiskOps™ also supports manufacturers and HDOs by centralizing risk assessments, tracking vulnerabilities, and facilitating collaborative decisions on delayed patches or alternative measures[1].

EU MDR Requirements for Medical Device Patching

EU MDR Legal Framework for Patching

The European Union Medical Device Regulation (EU MDR 2017/745) weaves software updates into its broader safety and lifecycle requirements. Annex I General Safety and Performance Requirements (GSPRs) serves as the foundation, ensuring that medical devices - software included - remain safe and effective throughout their lifecycle. It also mandates minimizing risks and safeguarding against unauthorized access or tampering[1][2]. This makes cybersecurity patching an essential element, requiring careful planning, justification, and documentation.

Rule 11 under Annex VIII significantly impacts standalone medical device software by classifying most of it as Class IIa or higher, with higher-risk software (like diagnostic or therapeutic tools) often falling under Class IIb or III[3]. This classification demands stricter regulatory oversight for software changes and patches. For higher-risk classes, manufacturers must validate patches thoroughly, assess their clinical and cybersecurity impacts, and involve Notified Bodies when changes might affect safety, performance, or intended use[6][4]. Even minor cybersecurity updates for Rule 11 software require detailed impact assessments, regression testing, and traceable documentation to ensure risks remain acceptable[1][3][5].

The technical documentation outlined in Annex II and III plays a crucial role. It must detail the software's architecture, configuration management, cybersecurity controls, known vulnerabilities, and the manufacturer's update strategy across the device's lifecycle[2][5]. This includes explaining triggers for patches, development processes, risk assessments, and communication strategies for deployment[1][2]. Furthermore, this documentation must be continuously updated, showing clear links between patches, risk management outcomes, and post-market surveillance findings specific to EU requirements[2][3][5].

Patching in the EU MDR Lifecycle

EU MDR emphasizes a proactive post-market surveillance (PMS) system to monitor device performance, including cybersecurity vulnerabilities and incidents, as well as the effectiveness of patches in the field[2][4]. Security updates should be informed by PMS inputs like user complaints, vulnerability reports, penetration testing results, and real-world data. The PMS plan must outline how these inputs lead to corrective or preventive actions (CAPA), including patches[1][4][5]. For software-based devices, manufacturers must show how PMS data drives patch prioritization, risk evaluations, and design updates, ensuring a continuous feedback loop between field data and lifecycle maintenance[2][4].

Vigilance reporting obligations under EU MDR require manufacturers to report serious incidents and field safety corrective actions (FSCAs) related to cybersecurity to Competent Authorities[1][4][5]. If a security patch qualifies as an FSCA - such as an urgent update to prevent harm - manufacturers must issue a Field Safety Notice, document their rationale, and ensure timely notification and implementation[1][4].

For devices classified as Class IIa, IIb, and III, Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs) are required to summarize safety and performance data, including major software changes, cybersecurity events, and corrective actions like patches[1][6][4]. These reports should include trend analyses of cybersecurity complaints, the number and types of patches deployed, and their impact on the device's risk-benefit profile[1][4]. PSURs and PMS reports must also address any delays or challenges in deploying patches, lessons learned from incidents, and planned improvements to the update process[2][4].

Change Control and Documentation Under EU MDR

EU MDR requires a structured change control process built on PMS data and patch triggers. Manufacturers must have a change control process that evaluates all software updates - including security patches - for their impact on the device's intended use, performance, risk profile, and compliance with essential requirements[2][3]. Criteria must be established to differentiate minor changes (like non-safety-related bug fixes) from significant changes that might need Notified Body review, updated clinical evaluations, or new conformity assessments[2][4]. Each patch must be logged with version details, a description of changes, risk assessments, verification evidence, and regulatory justifications[2][3][5].

Configuration management is critical for maintaining traceability of software versions and patches[2][3]. This includes maintaining a software bill of materials (SBOM), versioning protocols, environment baselines, and records of which patch levels are active on specific devices. Effective configuration management allows manufacturers to quickly identify affected devices in the event of a new vulnerability or FSCA and demonstrate compliance to Notified Bodies and auditors[2][3].

When patches alter device behavior, cybersecurity measures, user workflows, or risk mitigation strategies, manufacturers must update instructions for use (IFU) and manuals accordingly[2][4]. This includes ensuring all language versions are updated consistently, withdrawing outdated instructions, and tracking the distribution of updated materials - especially for critical security patches that impact patient safety[2][4].

Healthcare delivery organizations managing EU MDR-compliant devices can improve compliance by using platforms like Censinet RiskOps™. These tools centralize risk assessments, track medical device vulnerabilities, and streamline collaboration with manufacturers on patch deployment and validation[1][5]. By aligning manufacturer patch processes with healthcare organization risk management, these platforms provide real-time visibility into patch status, residual risks, and compliance evidence, supporting both EU MDR requirements and broader cybersecurity governance across markets in the U.S. and EU[1][5].

FDA vs. EU MDR: Key Differences in Medical Device Patching Rules

FDA vs EU MDR Medical Device Patching Requirements Comparison

Understanding the differences between FDA and EU MDR regulations is crucial for creating a global approach to patch compliance.

Structural and Governance Differences

The FDA operates as a centralized federal agency, handling premarket submissions, granting clearances and approvals, and enforcing cybersecurity regulations like 21 CFR Parts 803 and 806. This centralized system offers clear guidance, focusing on areas such as threat modeling, Software Bill of Materials (SBOMs), and coordinated vulnerability disclosure. This setup makes it easier to roll out routine patches quickly. On the other hand, the EU MDR relies on a decentralized network of Notified Bodies and national Competent Authorities. This structure can slow down patch approvals, especially for updates classified as significant.

For manufacturers, this difference is critical. Under the FDA, routine security patches that don’t affect a device’s intended use can often be deployed quickly. However, under the EU MDR, significant updates often require review by a Notified Body, which can delay deployment. The availability of Notified Bodies can further extend these timelines, creating additional hurdles for manufacturers operating in the EU.

These structural contrasts lead to differences in patch triggers and regulatory timelines.

Triggers and Thresholds for Patching

The FDA separates routine cybersecurity patches from software changes that could impact a device’s safety, effectiveness, or intended use. Routine patches - like updating third-party libraries or improving configuration security - don’t usually require a new premarket submission, provided risks are well-documented and managed.

In contrast, the EU MDR doesn’t explicitly differentiate between routine patches and functional updates. Instead, every software update is evaluated to determine if it constitutes a significant change in design or intended purpose. Cybersecurity updates must be reflected in the risk management file, clinical evaluation (if applicable), post-market surveillance (PMS) processes, Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs), and technical documentation. If deemed significant, these changes might require review by a Notified Body, updates to certification, or even a new conformity assessment. Additionally, software classified as Class I under FDA rules could be designated as Class IIa or higher under the EU MDR, exposing it to stricter scrutiny.

These varying thresholds directly influence manufacturers’ post-market surveillance and reporting responsibilities.

Post-Market Obligations and Timelines

Post-market surveillance expectations also differ significantly. The FDA requires manufacturers to have a cybersecurity risk management process, including ongoing vulnerability monitoring, coordinated disclosure, remediation plans, and risk controls. Reporting under 21 CFR Part 806 is only necessary when specific thresholds - such as deaths or serious injuries - are met. In such cases, manufacturers must report incidents within 30 days.

The EU MDR, however, demands a more formalized and continuous post-market surveillance system. Manufacturers must maintain a PMS system, produce regular PSURs for higher-risk devices, and adhere to strict vigilance reporting requirements for serious incidents, including cybersecurity events that could affect safety or performance. Unlike the FDA’s event-driven approach, the EU MDR emphasizes continuous clinical data collection and structured reporting to Notified Bodies. Serious incidents must be reported to Competent Authorities without delay, and manufacturers are obligated to carry out Field Safety Corrective Actions (FSCA) and trend reporting.

To navigate these complexities, manufacturers need integrated systems for timely vulnerability detection and jurisdiction-specific reporting. While the FDA focuses on event-driven reporting with a 30-day timeline for adverse outcomes, the EU MDR requires ongoing surveillance, immediate notifications, and detailed PSUR submissions. Legacy devices add another layer of complexity in the EU, often requiring updates to existing risk management protocols.

sbb-itb-535baee

Building a Harmonized Patching Compliance Strategy

When navigating the patching requirements across different regulatory frameworks, a unified approach can simplify compliance efforts. By grounding processes in globally recognized standards and tailoring them to meet specific jurisdictional needs, manufacturers and healthcare organizations can create a streamlined strategy that satisfies both regulators.

Risk-Based Governance for Global Compliance

A global compliance strategy should be built on key standards like ISO 14971 (risk management), IEC 62304 (software lifecycle), and IEC 81001-5-1 (health software cybersecurity). A single, global cybersecurity plan with market-specific add-ons can help avoid inconsistencies during audits. This plan should cover the entire process - vulnerability intake, risk assessment, development, validation, deployment, and monitoring - while aligning outputs to meet FDA requirements (e.g., 21 CFR Part 806 reporting) and EU MDR obligations (e.g., PMS plans, PSUR updates, and Field Safety Corrective Actions).

To ensure consistency, establish a centralized vulnerability and patch review board that includes representatives from regulatory, clinical, quality, and engineering teams. For every vulnerability and proposed patch, the board should:

- Document an ISO 14971 risk analysis to evaluate pre- and post-mitigation risks.

- Implement software changes following IEC 62304 procedures, including regression testing and release criteria.

- Apply IEC 81001-5-1 security controls, such as authentication, integrity checks, and logging.

Decision gates should then determine whether a patch qualifies as a routine security update or a significant change requiring new submissions, technical documentation updates, or Notified Body involvement. These criteria should align with both FDA and EU MDR regulations.

This governance model naturally leads to detailed and traceable documentation practices.

Documentation and Traceability Best Practices

Regulators demand clear connections between vulnerabilities, risk assessments, design updates, verification evidence, deployment details, and post-market performance. To meet these expectations, manufacturers should maintain a detailed "patch record" for every released update. This record should trace:

- The originating vulnerability (e.g., CVE identifier or field incident).

- The ISO 14971 risk analysis.

- Design and software change records under IEC 62304.

- Verification and validation evidence, including cybersecurity-specific tests.

- Field deployment data, such as adoption rates and residual risks.

A single change control identifier should link all relevant documentation, including the design history file, device master record, EU technical documentation, and risk management file. This ensures auditors can easily trace one identifier through all related artifacts.

For FDA compliance, traceability must address whether a change triggers a new 510(k), PMA supplement, or 21 CFR Part 806 reporting. For EU MDR, it must support Notified Body reviews, PMS/PSUR updates, and vigilance assessments. Templates can help ensure consistency by evaluating clinical, cybersecurity, usability, and regulatory impacts. Manufacturers should also define patch categories - such as emergency security patches, routine updates, or maintenance releases - along with associated risk criteria (e.g., patient safety impact or PHI compromise) and target response times for each category.

Given the complexity of managing centralized documentation across both frameworks, cyber risk platforms can be a game-changer.

Using Cyber Risk Platforms for Patching

Cyber risk platforms provide the tools needed to centralize inventory, track vulnerabilities, and maintain documentation for both FDA and MDR compliance. A platform like Censinet RiskOps™ offers a cloud-based system that consolidates vulnerability tracking, patch status, vendor notifications, and third-party risks into one seamless workflow. This eliminates the need for spreadsheets and enables secure sharing of cybersecurity data within collaborative networks.

"Not only did we get rid of spreadsheets, but we have that larger community [of hospitals] to partner and work with."

- James Case, VP & CISO, Baptist Health

For manufacturers, platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ simplify regulatory submissions and audits by organizing risk assessments, change impact analyses, and field performance data. Healthcare organizations benefit from real-time insights into device vulnerabilities and patch availability, enabling smarter, risk-based decisions that balance cybersecurity needs with clinical workflows.

"Censinet RiskOps allowed 3 FTEs to go back to their real jobs! Now we do a lot more risk assessments with only 2 FTEs required."

- Terry Grogan, CISO, Tower Health

This kind of efficiency is especially valuable when juggling the documentation and coordination demands of meeting both FDA and MDR requirements.

Conclusion

Both the FDA and EU MDR require lifecycle patching to ensure medical device safety, but their approaches differ significantly. The FDA provides a centralized, detailed framework with clear guidance on cybersecurity measures, such as vulnerability disclosure, threat modeling, and timely updates. In contrast, the EU MDR embeds patching into broader risk management and surveillance activities, emphasizing alignment with standards like ISO 14971 and incorporating elements like PMS plans, PSURs, and vigilance reporting, though with less specific guidance on execution.

Their governance structures also vary. The FDA acts as a single federal authority, offering consistent oversight, while the EU MDR relies on a network of Notified Bodies and national authorities, introducing variability in expectations and timelines. This distinction influences the management of post-market activities. The FDA focuses on Medical Device Reporting and corrections under 21 CFR Part 806, whereas the EU MDR requires detailed PMS plans, periodic safety updates, trend analysis, and field safety corrective actions for addressing safety-related patches.

Despite these differences, both frameworks aim to protect patient safety through timely, risk-based patching. Manufacturers can meet the requirements of both systems by implementing a unified, lifecycle patching program rooted in ISO 14971 risk management and IEC 62304 software lifecycle standards. Such an approach not only reduces redundant efforts but also streamlines audits by linking patches to vulnerabilities, risk analyses, and verification processes. This ensures smoother regulatory interactions and faster remediation efforts across both jurisdictions.

To make this harmonized strategy actionable, practical tools are invaluable. Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ centralize vulnerability tracking, risk assessments, and regulatory documentation, simplifying compliance for healthcare organizations and vendors. By managing risks across medical devices, clinical applications, and supply chains, these tools support the lifecycle framework required by both the FDA and EU MDR while easing the burden of regulatory compliance.

FAQs

How do the FDA and EU MDR differ in their medical device patching requirements?

The FDA prioritizes pre-market approval for medical device updates, requiring detailed documentation, thorough validation, and regulatory review before any patch or update can be released. This process ensures that all updates meet rigorous safety and performance standards prior to being made available.

On the other hand, the EU MDR leans heavily on post-market surveillance and risk management. In this framework, patching is seen as part of the ongoing compliance and lifecycle management of a device. This approach allows manufacturers to address risks and roll out updates more flexibly after the device has already been deployed.

The primary difference lies in their strategies: the FDA focuses on upfront approval, while the EU MDR emphasizes continuous monitoring and post-market updates. Both aim to ensure safety and reliability but approach it from distinct angles tailored to their regulatory philosophies.

What steps can manufacturers take to comply with FDA and EU MDR patching requirements for medical devices?

To meet the patching requirements set by the FDA and EU MDR, manufacturers need to take a proactive and detailed approach to risk management. This involves a few crucial steps: keeping precise and up-to-date records of all patching activities, conducting regular vulnerability assessments, and establishing strong change management processes to handle potential risks effectively.

Using healthcare-focused risk management platforms can make this process more manageable. These platforms streamline tasks like cybersecurity assessments, monitoring regulatory requirements, and staying aligned with changing standards. By adopting this strategy, manufacturers can better protect patient safety while ensuring they remain compliant with regulations in both regions.

How do global standards like ISO 14971 and IEC 62304 support consistent medical device patching strategies?

Global standards like ISO 14971 and IEC 62304 are essential for shaping how medical device patching strategies are handled. They provide structured frameworks focused on risk management and software lifecycle processes, helping manufacturers and healthcare providers stay aligned with both FDA and EU MDR regulations.

Sticking to these standards ensures a consistent method for identifying, evaluating, and addressing risks tied to software updates and patches. This approach not only supports regulatory compliance but also strengthens patient safety and boosts the reliability of medical devices across various regulatory landscapes.